The Shakespeare's Head + the New World Order

Each of us seems to be taking some kind of steps to adapt to these changing times Will we make it?

The words have slowed to a trickle these days. Like a tap that is clogged with debris — nothing seems to want trickle out If an editor put a gun to my head now and said “I want 3,000 words on your favorite story that you have been pitching for five years,” I’m not sure I could even pull it out of me.

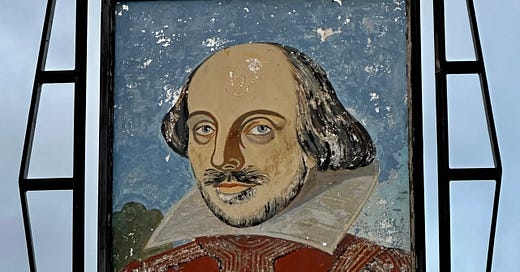

But first, the pub of the month. The Shakespeare Head isn’t Victorian or ornate or plate-glass beautiful or really unique, except — and this is what I love about it — it doesn’t try to be. It doesn’t have any compunction about being in a trendy neighborhood or trying to attract the smart set, as the hipsters were once called. The quintessential boozer from the 1960s, the Shakespeare’s Head doesn’t need to have a “Karl Mark Drank Here” reputation or a fancy mixologist — the bartender is about 75, bald and takes his sweet time serving customers — but because of the pub’s unconcerned attitude, no one bothers. They can see you and you can wait. Plus, absolutely nothing beats that faux-sailing theme — replete with anchors and buoys — that is rarely found, especially outside seaside towns — these days. While the 1970s-dentists-office archaeological -vibe may send customers in the other direction, don’t fret: the tenders of these salt-of-the-earth local extend a warm welcome to all — even the bald guy who takes 10 minutes to find your crisps.

Trump + My Broken Promise

Back in the old journalism school, we had a bushy haired, wooly eyebrowed professor named Sandy Padwe who was a sports-turned-investigative journalist when, in the mid-1980s, he exposed the Pete Rose betting scandal. On certain days, post-9-11-2001, he would look toward South Manhattan where the remains of the World Trade Center continued to smoke, and say something to the effect of “just you wait, all the asbestos in those buildings and the workers exposed to it, is going to cause massive illiness.”

Padwe, as we called him, was right. To date, more people have now died from the toxic exposure of the World Trade Center than in the 9/11 attacks: 4,343 survivors and first responders. It's not that Padwe enjoyed wagging the finger — although, let’s just admit it, a lot of us journalists quite enjoy a little “I told you so.” Rather, Padwe wanted to point one of us aspiring writers to a story that would not only expose a wrong, but also possibly prevent some terrible things from happening.

Last summer I pulled a Padwe. I returned from the States and penned a 10,000-word cautionary tale on my ten days spent in Iowa (a mostly steady Trump state) and all the troubles that particular state as a microcosm of the rest of the country, could face. I am not sure how many people read it, or even if old Padwe had a look. Doubtful. I wrote my story, brushed my hands and said that was the end of my Trump writing for this term.

But about three weeks ago, Columbia Journalism School held an off-the-record meeting with its students to discuess matters of free speech. The message that night seemingly came down to, in essence, “do what you feel like you need to do, but no one can protect you, these are dangerous times.” The following day, a reporter from the New York Times reached out to verify the comment from Dean Jelani Cobb. Cobb did say it — supposedly out of context — but here it is, verbatim:

“I responded that those words were technically accurate but practically misleading... I went on to say that I would do everything in my power to defend our journalists and their right to report but that none of us had the capacity to stop DHS from jeopardizing their safety….”

I have so far done my best to ignore freedoms stripped away one-by-one, the enormous U.S. tariff trade war, federal employees’s forced resignations, immigrants on deportation flights to nefarious countries known for human rights abuses, the Trump/Gaza plan, the business dealings over Ukraine’s war, and everything that would have had the U.S. President thrown out of office faster than an Southern-American can say “Nixon/Agnew.” I haven’t written a social media post, a blog, an article, a comment or much of anything about the situation. In fact, my European and English friends and I generally avoid the topicor Trump altogether.

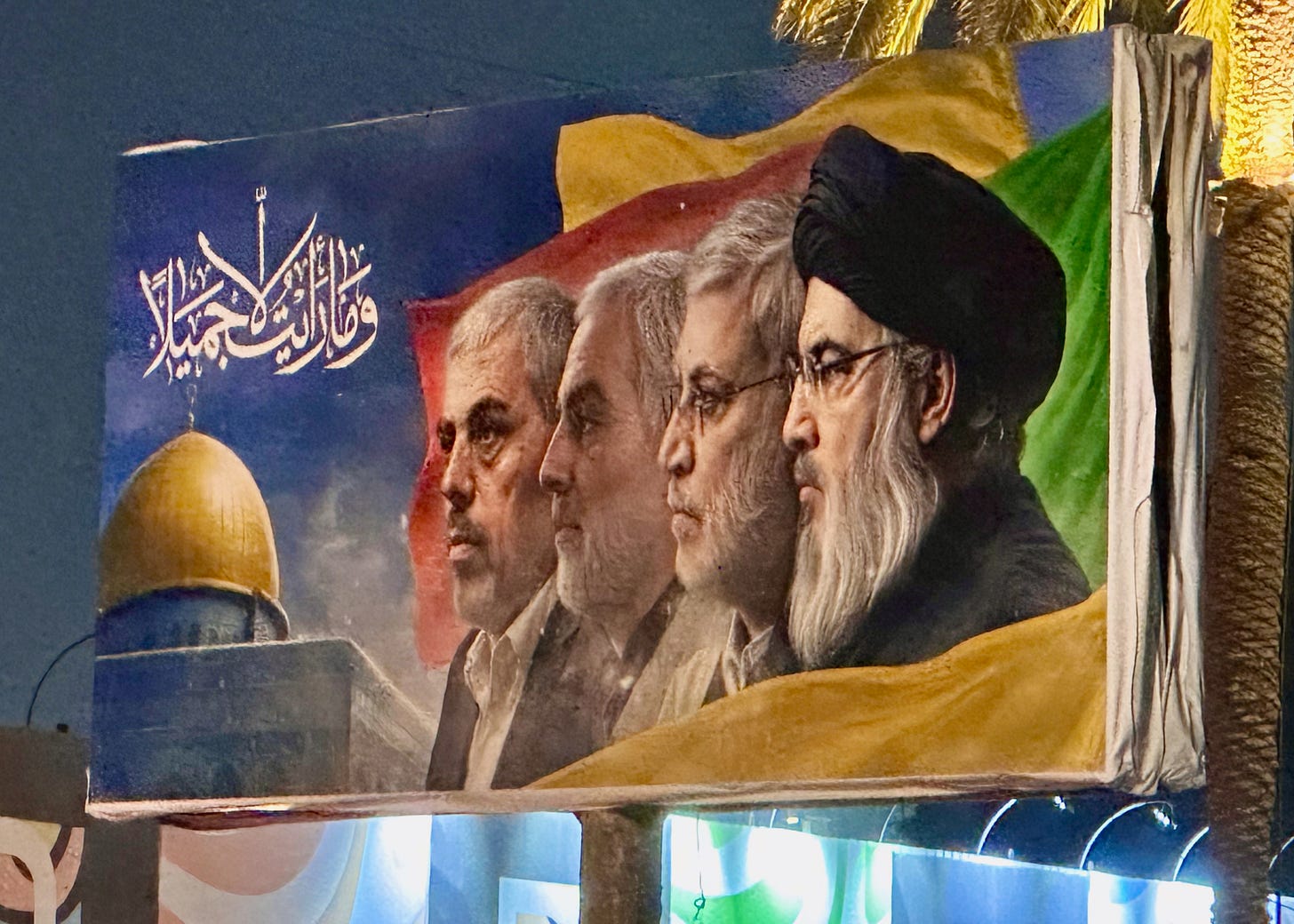

Despite these policies and these “protective” speeches given at my own alma mater — talks that raise the personal fury metter arrow — instead of turning toward journalism, I seem to be just turning away. Quite possibly my recent trip to Baghdad took away my focus, or the recent death of my favorite aunt, who was raised in 1950s cancer-chemical soaked Iowa, from metastatic cancer have made my words feel futile.

Depression is one of those things that goes hand-in-hand with creativity: the writer’s melancholy, right? Mine can get to the hide-under-the-covers and not want to leave my apartment stage, if I let it go for a while. But it generally starts as a mild irritation, followed by sulleness and withdrawal. The anger then hits: it can be ugly, rude, combative — my depression makes me wants someone to feel some pain if they fuck with me or something I care about. Sometimes, that is productive — or motivating, at least. I have done many stories in which anger at systems, policies and injustice have gained me a raised Padwe eyebrow (see above) of approval.

I guess it wouldn’t be the first time a personal depression segued into a national — or now, international malaise — for me, but the older I become, the more difficult it is for me to spill words over these matters. Twenty years ago, I stood in the bone-chilling cold winter of 2003 writing about ani-war protests, believing that my reporting on a group of vocal, active people could help stop a war. After the U.S. started a predictably disastrous 20-year bloodshed and throughout many visits to the refugee-laden Middle East, in addition to watching the ascendancy and escalation of, literally, thousands of voices (isn’t Substack supposed to be a platform for all those people who don’t have agents or major magazine-and-book deals, btw?), I have begun a gradual descent into feeling that my informative essay, or my blog or my scream or sob is just one more into a deeper well of increasing width. If I allow it, I feel as if it could swallow me entirely

I don’t want to turn away from Professor Padwe and the thing that has felt like my calling since I was age five. That said, I have learned that I cannot pitch from the ground in Iraq or Uzbekistan or wherever I am and expect editors in New York or London in thier high-rises and expect them to necessarily care. They don’t see a story the way I experience it, and besides, they need to sell magazines, with celebrity narratives, photo shoots of designer goods, the enjoyment of life — bringing us all from our increasingly repressive existence into one to which we supposedly dream.

To that end, instead of just writing stories, I have decided to choose a few causes about which I care, write about them (if it happens) and then actually do something, whether it’s organise a group of animal professionals into the Iraqi Street Animal Rescue Organization to help rescue dogs and cats off the streets of Iraq or try to find equipment for the Iraqi Foundation for Sport + Development to help kids get out of the camps and find a future for themselves.

In the end, Sandy Padwe’s shrugs and finger wags weren’t journalism calls to arms or gifts of stories to inquisitive minds. They were appeals to do something about the situations we face on a daily basis. They were predictions about the future if we didn’t act. So far, I believe we are now getting to a collective state of under-the-bedclothes denial; we all need to do Padwes in whatever forms those may take.