RAGBRAI After the Caucuses. Biking across a Red State in an Election Year (Entirety)

What happens when people vote against their interests? Town to town, it's evident in Iowa

We are pausing our regularly scheduled programming for a special election essay. In addition to voting, after canvassing the state of Iowa in July 2024 for the (Des Moines) Register’s Great Bicycle Ride Across Iowa (RAGBRAI), I penned a 10,000-word essay on the reasons a vote for Trump is a vote against American and international interests, as I saw it across Iowa.

I will be on Cape Talk’s “Morning Breakfast” tomorrow at 7am, GMT-1,(3am EST) for a talk about the election as I see it, more about the issues, rather than the candidates’ personalities, although I am certain there will be some of that, too. https://omny.fm/shows/capetalk-breakfast

It’s a vehicle distinct in its size, breadth and ingenuity — and other than across Iowa during the last week of every July, onlookers will likely never see it on any other occasion. The design is simple: take a school bus, set an extra-long steel platform on its top and find a set of homemade winding stairs. Weld the plate to the top of the bus and add slots for every make, model and type of bicycle, then place the winding stairs from the back of the bus to its roof. Paint the bus an eye-catching purple, yellow or green, come up with a pithy name — Shagbrai, The Dawg Pound or Cold Babies for example — and voila, the vehicle for RAGBRAI, the (Des Moines) Register’s Great Bike Ride Across Iowa, is ready to carry a gaggle of eager cyclists for the annual trip through Everytown, America.

I first encountered these buses during the annual 2014 RAGBRAI, which I had volunteered to do with my father. Ten years ago, there were only a handful of them, and I didn’t pay much attention to their particular style. I was concentrated on getting along with my father — 30 years my senior and an attorney who was hypercritical of my seemingly endless (and non-paying) struggle as a journalist — in addition to pedalling through the eighty-plus miles per day to make it from roughly Council Bluffs Iowa, where we dipped our back wheel into the Missouri River, to Davenport, Iowa, where we finished by christening our front wheel in the Mississippi River. In 2014, Dad and I didn’t make it through the ride, as he was T-boned by another rider mid-week and broke five ribs. Being the hearty Iowan descendant of Germans — as a good percentage of Iowans — my father was treated, had his broken helmet replaced and carried on for twenty-five more miles before deciding that pain trumped gain, and we quit the ride early.

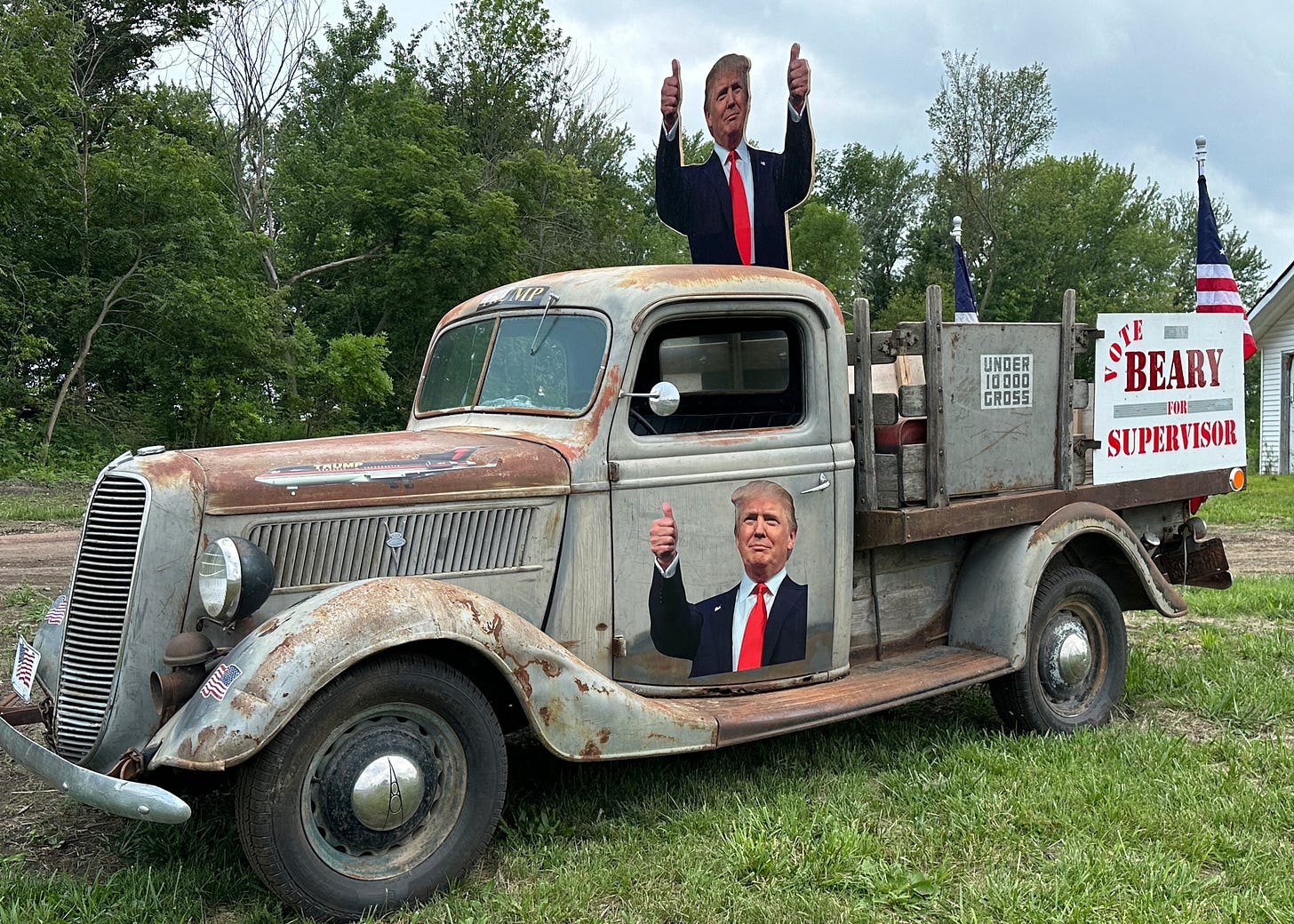

In ten years, life had changed quite a bit in Iowa — in America — and in my family. Back in 2014, Donald Trump was at least a year from announcing his candidacy for president, and America was about as normal as it could get. This past summer, as I walked around the mega Wal-Mart parking lot in Winterset, Iowa and looked at the large, colorful buses multiplying at the end of a day of seemingly endless driving by factory farm after factory farm, fertilizer plant after fertilizer plant, and elaborate life-size Trump display after elaborate life-size Trump display, I realized that in this election year, Iowa was a microcosm of the divided country, even more chaotic than in 1973 when Richard Nixon resigned and Gerald Ford assumed office. Or 1986, when farmers overborrowed, riding high on export grain prices and plunged their livelihoods into bankruptcy. Or in the 1990s, when the first and second generations of German immigrants started dying off with no one to replace them in the homes and towns they left behind.

RAGBRAI begun in 1973 as a dare between two journalists in a newsroom. Des Moines Register feature writer/copy editor John Karras, an avid bicyclist, suggested to Don Kaul — the author of the Des Moines Register’s “Over The Coffee” column — that instead of sitting in a newsroom in Washington, D.C., where he lived and worked, that Kaul set out and write columns about life in Iowa from behind bicycle handlebars. Kaul countered: he would ride across Iowa if Karras rode with him. Karras agreed and invited “a few friends” to ride with them from Sioux City to Davenport from August 26-31. Camping and eating stops were scheduled in Storm Lake, Fort Dodge, Ames, Des Moines and Williamsburg.

Thanks to only six weeks and little promotion before Karras and Kaul took off for their ride, only an estimated three hundred people showed up in Sioux City. About more than one hundred riders pedalled the entire distance that first year, which was fortunate for the Register, as no one had either driven the route or made any sort of overnight arrangements, camping or otherwise. At one point — between Des Moines and Ames — the day ride swelled to five hundred and among those, Clarence Pickard of Indianola, stood out. The eighty-three-year-old hadn’t ridden a bicycle in about twenty years and turned up with a used ladies Schwinn, but he cycled the three hundred miles to Davenport. Pickard’s attire: a long-sleeved shirt, trousers, woollen long underwear, and a silver pith helmet.

Kaul’s and Karras’ articles and columns about Iowa town life and the other characters they met along the way became one of the most popular sections of the newspaper. Letters and calls poured in from across the state. Iowans asked for the Register to hold RAGBRAI again, but a month earlier so that it didn’t coincide with the first week of school, as well as the final weekend of the Iowa State Fair. The Register scheduled “SAGBRAI,” the Second Annual Great Bicycle Ride Across Iowa, for August 4-10, 1974. For the next fifty years, Kaul, Karras and the Register’s coordinators have arranged the bike ride along dozens of West to East routes through 780 Iowa towns, hosted 326,650 people and logged 19,542 total miles In fact, the ride has become so popular that RAGBRAI officials now limit the number of week-long riders to 8,500 in order to maintain “a sense of control” and fewer injuries.

My father knew nothing of RAGBRAI until it had been running for nearly thirty years and he was fifty-five. Dad had moved from his parents’ farm in Southeast Iowa to attend law school at the University of Tulsa, and after his graduation, he helped my mother attend and also finish. After they divorced, he met my late stepmother, an Oklahoma native eighteen years his junior and another student at the University of Tulsa Law School; she became his legal intern. Nothing like the stereotypical vision of a bumbling, blonde, buxom temptress, my late stepmother, Annette was actually quite nerdy — she and my father planned on practicing law together until she hit age forty-five when they would both quit law and see the world. Following one of their many trips t, Annette saw a story about RAGBRAI while browsing through a Southwest Airlines magazine. They should ride it together in 2000, she said; she would train and “get in shape for it.” Annette died in a car accident in September 1999 — just two months after her 36th birthday — while she was driving home from the personal trainer. My dad decided to ride RAGBRAI in her memory. But he kept on going… year after year after year after year.

I wasn’t around for the first thirteen RAGBRAIs, choosing to avoid the heat of Iowa summers, as well as the multitudes of family engagements. But I heard stories of him forming a team with some of his Catholic church buddies, Team Truants (one of my father’s successful attempts at using an Oxford-dictionary word to make a joke), stopping for lemonade and cookies with my grandmother, snapping a photo with the baseball-playing ghosts from Field of Dreams, riding to Davenport or Burlington or Fort Madison and finishing the seven-day journey with cases of Busch and Natural Light. My younger sister, an attorney in Oklahoma, went along with Team Truant several times, and even earning a highlighter yellow “Team Truant” bicycle jersey. I was content looking at photos. My brother had also escaped duty thus far, managing to use his successful real estate business as an excuse to avoid the ride. But in 2014 I had been through a bad break-up; I was between UN contracts; and my sister had just given birth to her second daughter.

Other than the internal disruption of a woman riding fifteen miles an hour into my father, the occasion was — on the outside of our small world — uneventful. Barack Obama was president; Joseph Biden was vice-president. The tensions in the Middle East kept flaring, but the Islamic State had yet to rear its ugly head. Orphaned migrant children had come to Iowa from the Southern U.S. border, but people were stepping up and welcoming them — or at least tolerating them. The United States didn’t have an orange-haired reality star who used to mug for Pizza Hut stoking the internalized racism and Islamophobia of a consumerist electorate, a Tea Party turning into fascist Republicans, and a country so divided that politics became a preference on Match.com. The only sign (for me) in those weeks that the American patriarchy was alive and well was an instruction from my sixty-nine-year-old-white-male-attorney-father to his friend: “Don’t worry about waiting up for Adrian, Charles, she will be well behind you.” I had to stop at every rest stop to make sure the friend, a Tulsa-based news anchor named Charles Ely, had not collapsed.

A little more than two years later, the United States became a version of itself that not even I, a former Republican-prep-school-kid, could recognize or explain. The Tweets of an deranged man became daily news and the populist candidate gave an unhinged populace permission to listen to the devil on their shoulder when social issues, such as immigration, care for the poor, police brutality, racism and later on, vaccinations and mask-wearing, arose. I found good work reporting on Trump and the daily news for a South African talk news station with serious presidential schadenfreude, but when my English partner lost her job at a business travel company in 2020, we decided to find a better way of life. We chose home for her: London.

I knew the Brits and Americans shared most parts of a common language, but little else. Because I already liked “socialism light” — an alternative to the hyper-capitalism of the States — I took nicely to the green spaces, the proximity to Europe, the old buildings, trains that went almost anywhere at most times, the ethnic feel of new immigrant neighborhoods and of course, the health care. The people posed another challenge. They didn’t care for Americans that much, and while the rigidity of the English annoyed me, the distaste for American values and American exceptionalism sunk into me. By the time Dad and I arrived for RAGBRAI 2024, I noticed that I had lost tolerance for Midwestern Americans. I had spent one day in Oklahoma.

Once we finally reached West Des Moines, Iowa and RAGBRAI, I knew I had to write my thoughts, town-by-town, ala Karras and Kaul, of the ride across the Hawkeye state — a state once made up of millions of German, Dutch and other immigrants, as well as Native Americans; a state that collective fought against slavery in the late 19th century; a state that welcomed Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies; and a state known for its wide range of political viewpoints. Among the towns, I realized that not only was Iowa important because of its caucuses in election years, but also because every town symbolized all of the problems in America and the potential of a Trump presidency to exacerbate them.

Day One, Glenwood to Red Oak: Factory Farming + Education

My father, by now, is a great-uncle, and he is an active one. He has attended high-school graduations, college commencements, weddings and births of not only my cousins, but also my cousins’ children, few exceptions. Now age seventy-eight, my father decided to attend the family wedding of my cousin’s daughter, followed by his annual RAGBRAI ride beginning July 20, 2024. In London, on the phone with him in late June, Dad mentioned that every member of Team Truant (except my sister) had bailed out. I also realized that my sister, who had lived in Oklahoma for twenty years following law school, was burned out. I opened my mouth, closed it, opened it and then hesitantly and quietly said, “I will drive the SAG wagon for you.”

He went into immediate action. Flights were arranged, bicycles were loaded, Trump was almost assassinated and three days later I landed in Oklahoma. The first thing Dad did when I dropped my bags in his apartment was to turn on the Republican National Convention. “It’s just good to know what these people are thinking,” he said, justifying his fascination or horror or bemusement at seeing the yellow-haired man in the big red tie with the square gauze over his ear talk for nearly two hours. The next morning, we drove to West Des Moines, Iowa, passing dozens of Trump 2024 yard signs along the way.

What is West Des Moines, I wondered, pulling into a melange of big-box stores, PF-Chang’s, and strip malls? Is it part of Des Moines proper? Is it its own little city? And is Des Moines, Iowa, big enough for a West and other? None of these questions were answered during the party put on by the family of the bride, a human relations associate at Progressive Insurance, and her husband, the heir to an industrial cleaning company. While Des Moines is the capital — and the place where the madness of the 2024 election began — West Des Moines is the affluent suburb of Des Moines, which is already the number one city in the nation for its insurance industry and financial-services, as well as raising a family. Yet, next to the city of 211,000, lies a small metropolis of 68,723 people — a number that has increased by about twenty percent from 2010. And despite being a prominent part of the once Sac and Fox nation, West Des Moines is eighty percent white, four percent Black and five percent Latino.

West Des Moines affluence is the direct beneficiary of advanced manufacturing — Iowa's largest industry, contributing $30 billion to the state each year. About four thousand manufacturing facilities employ fifteen percent of Iowa's workforce, many delivering products to serve the agriculture industry. This growth marks a significant change from forty years ago, when the term “factory farming” would have baffled my grandfather, as well as my father’s large family of German farmers, which had left the North Rhine-Westphalia region during unification to start small subsistence operations — only to encounter the boom-and-bust economy of grain exportation seventy years later. In those years, as President Jimmy Carter fought the Cold War, an acre of Iowa land ballooned from $419 in 1970 to $1,958 in 1979. Farmers could — and many did — borrow against the value of their land. They had options to send their children to college and buy equipment to expand their operations so those same children would have a place when they returned. But when Carter forbade the sale of grain to the Soviet Union for its invasion of Afghanistan, the price-per-acre of Iowa farmland fell by more than seventy percent and those farm families’ high-interest loans far exceeded the value of their land. By then, the family farm no longer held much attraction to ambitious Baby Boomers, such as my father, yet certain dutiful sons reluctantly accepted their birthrights. Those who lasted the longest, and who survived foreclosure, took their subsidies, consolidated their lands and grew their operations.

It worked.

No state in the United States produces more meat than Iowa. Nor does any other top the rest of the country in the production of eggs, soybeans, and corn. With more than twenty-three million pigs, according to United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the animal outnumbers Iowans seven to one. Chickens could overrun Iowans at a rate of over sixteen to one. All of these animals are raised on enormous, densely packed facilities known as Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) — the Factory Farms. CAFOs strive to maximize output while minimizing costs, largely by taking away land for grazing, nesting, and other animal behavior. But CAFOs also increase animals’ risks of contracting diseases, such as pneumonia, salmonella and flu, and those birds and swine and cows crammed into wire cages or metal crates, inside dirty, enclosed sheds cause noxious gases — hydrogen sulphide, ammonia, and nitrates — resulting in asthma, heart attacks, cancer, and high rates of infant mortality.

In the early 1980s, my ambitious uncle, Thomas Fullenkamp, a great-great grandson of one of Southeast Iowa’s first major landowners, hit on the right formula of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, adding “micronutrients,” such as zinc, calcium and boron, and called it Golden Furrow Fertilizer. To that, he added a pesticide business and something called “precision agriculture consulting, and crop scouting” to build Golden Furrow. All four of my Uncle Tom’s children, when they tired of his side hobby in stock-car racing, joined the family company, whose sales and market share grew steadily through the nineties and early aughts. In 2015, Golden Furrow Fertilizer was acquired by Crop Production Services and finally Pinnacle Holdings, one of the largest agriculture businesses in the United States, operational in twenty-seven states. Family whispers point to a $45 million profit on the sale, which his children used to buy large homes and rural plots of land and his grandchildren used to attend college and move to West Des Moines, Iowa.

While the first 20-30,000 RAGBRAI cyclists trickled into Glenwood, Iowa on the Friday afternoon following the Republican National Convention for the ride’s fifty-first edition, my father, my sister and I drove his boxy Lexus-RX through Kansas to Des Moines and the wedding of one of the heirs of my Uncle Tom’s fortune. Sticking to German Catholic tradition, the wedding itself was held in the nearest parish church followed by a new twist from the local bank hall: a reception at the thirty-year-old Glen Oaks Country Club, one of about five in the region and the home-away-from-home for the children of the nouveau riche agriculture class. Developing weedless and spotless tracts of land next to pristine rows of crops has become a pastime of the farmer, if not the sport itself.

The reception was a vision of peonies. Possibly a thousand peonies sourced from one of many local florists in Iowa. They lined the country club driveway, the entrance, the three open bars, the patio stairs, the dance floor and after-dinner cigar bar. While Biden holed up in his Delaware home to ultimately decide that he would, indeed, drop out of the presidential race, wedding guests dined on pork, steak and chicken because to not have all three would “not be ensuring my guests are well fed,” the mother of the bride told us all. “And my guests were going to be well fed.” Everyone’s stomachs were full that evening, aside from the vegetarians. And nothing could have possibly ruined the bride’s day — except possibly her own cousin making her first public appearance as a trans woman. But no one discussed it. In fact, no family member discussed politics or policy or sexual orientation or anything controversial, full stop.

The next morning, Dad made the decision that his wine consumption the previous night trumped his desire to start the ride on Sunday with the eighteen thousand other week-long riders, so we spent the day looking around Des Moines proper: the Iowa Statehouse (or state capitol), built from 1871 to 1884 and the only five-domed statehouse in the country; as well as the Capitol East neighborhood, a formerly run-down enclave of immigrants and poor people now home to progressive bookstores with portraits of Woody Guthrie and Che Guevara among the shelves, as well as bohemian chic home stores and repurposed bicycle shops.

From Des Moines, we travelled to Ames — home to Iowa State University, which a few of my cousins attended to learn the modern agriculture industry. I had seen a listing on Atlas Obscura for the Grant Wood murals in the school library, which depicted the purity of family farm life in the 1920s. These days, Wood, made famous as a practitioner of Regionalism — the figurative painting of rural American themes to oppose European abstraction — as well as for his New Deal Public Works of Art Project might have painted over the toxic mud mounds and ponds of phosphorous water mixed with pig waste that now exist from the CAFOs. But by 1930, his American Gothic — one of the most famous paintings in American art — cemented the stoic gentleman farmer and his dutiful wife as America’s cultural answer to Da Vinci's Mona Lisa.

Wood would recognize neither Iowa nor Iowa state today.

At Iowa State, which has a $1.9 billion endowment provided mostly by individual graduates who receive a twenty-five percent tax credit for their gifts, the Alliant Energy Agriculture Innovation Lab provides eighty-five thousand square feet to tinker and toy with devices such as nitrogen sensors so that farmers perfect their fertilizer rates and increase their crop production, as well as Artificial Intelligence trackers that predict swine wean-to-finish mortality, thus supporting the pig industry. To further increase farm output, the college’s college of Veterinary Medicine has partnered with Merck’s Animal Health to produce RNA-based vaccines for new disease pathogens, including sapovirus, which causes diarrhea in young pigs, as well as the bovilis respiratory and clostridial vaccinations for herding cows. The university, which prides itself on its modern environmental advances, has also helped farmers, such as Rand and Tanner Faaborg, who once ran a CAFO for a pork producer, turn their former pig pens into retrofitted palettes for medicinal and other mushrooms, as well as clean up waste ponds. But these projects still don’t support their beneficiaries, let alone the university. “I don’t think people really understand the extent of that growth and the negative impact that it’s had on our rural communities,” Tanner Faaborg told the New York Times in August. “There’s been population declines, small towns in Iowa are dying. With consolidation comes efficiencies, but at what cost?”

Day Two, Red Oak to Winterset: Deurbanization, Tourism and Consumerism

On Monday, Dad finally caught that RAGBRAI spirit and decided to begin his 2024 journey in Red Oak. Like most of these former train depot towns, Red Oak had a central square with a 19th century courthouse, a bandstand, and several landmarked buildings dating back to Iowa’s settlement. The town centers once had everything that small town America needed: a parish church, a local grocer, a soda fountain, a Montgomery Wards store, a suit shop for the farmers and a boutique for their wives, and always a “corner tap” bar, where the farmers and the agriculture company sales reps could drink a Schlitz or and Anheuser Busch product and jaw about the crops, the hogs, or the Iowa Hawkeyes sports teams.

These economies of scale don’t exist any longer. “I heard the locusts came through early this morning,” said a regular, meaning the RAGBRAI riders, at the Hardware Hank everything shop where I stopped to buy a screw and a nut to fix the bicycle rack on the back of Dad’s SUV. “Yeah, they came, but it weren’t so bad,” was the reply from the salesman who found my tools and a backseat organizer to sort through all the junk in Dad’s truck after about a minute in the store. When the salesman noticed me going for the gigantic window-prop Wilson tennis racquet, he offered to take my photo. I stopped myself for a second, wondering if he supported Trump. But upon realizing that half my family in Iowa supported Trump, I let it go.

After the snap, the salesman asked if I played and pointed me upstairs to the tennis section of the Hardware Hank. There I was confronted by a wall of Wilson racquets, grips, balls, dampeners, score books from the 1980s, and U.S. Open bags from the early 2000s. “The owner is a big player,” he said. “He lives up the hill where all the rich people live — got his own court.” I vowed to find it, adding it to my mental To-Do list of all the weird American things to see in Iowa: Albert the Bull, a 45-ton, 28-foot-tall concrete replica of the perfect Hereford bull in Audubon; Elwood, the world's tallest concrete gnome in Ames; the American Gothic house in Eldon; the Vermeer Windmill in Pella; the World’s Largest Golden Nickel in Iowa City; the Field of Dreams movie set in Dubuque; and the All-Iowa Lawn Tennis Club — basically, a grass tennis court cut out of an old soybean field in Charles City —were on the list.

I had fallen into the plan of the ride: mass distraction — and it worked. RAGBRAI started as a barn-size dare, but the Iowa Tourism Office took the Register’s idea and… biked with it, seizing on the ride’s capacity to show off the state’s hundreds of towns and hamlets. (Many of them perfect backdrops for the Trump campaign.) Along each stop, journalists from the Register and other small city newspapers descended, writing articles that depicted Iowa as having more going for it than just corn and elections. They aimed to depict the state as the true purveyor of the American way of life — the dream that all of us German and Dutch people sought after Europe’s kaisers made us landless conscripts in their bloodthirsty land battles. Each year, the RAGBRAI organizers draw a different line bisecting Iowa to glean as much visitor dollars for town museums and sites as possible. One July, cyclists might take the north route and pass through Clear Lake where Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson died in a plane crash after giving their last concert at the Surf Ballroom on February 3, 1959, followed by Dubuque for the Field of Dreams movie set, with the ride’s end at Davenport and the “Quad Cities” for the German American Heritage Center. The next year, the course could be bang on central with stops at the German Hausbarn Museum — a reassembled 18th-century farmhouse from Schleswig-Holstein — the entire town of Pella, Iowa, which has Delft China in all its local Dutch Colonial shops, including the Jaarsma Bakery, and the Camp Algona POW Museum, built on the site of a base camp for 10,000 German prisoners from April 1944 to February 1946. This past July, the mass of cyclists rode straight through the towns I knew growing up, when my thrice diplomaed and newly divorced father would take the family back home to show off the kids and the new BMW.

Ultimately, I didn’t have the time to see much besides the roads and Big Box stores. Dad and I had planned to meet in the Wal-Mart parking lot of Winterset, in order to avoid the crush of riders downtown. I drove to the outskirts of the town of less than six thousand people, where developers had constructed all of those Big Box stores consuming America. Hungry, I ventured into the gigantic Wal-Mart, where a monstrous array of everything awaited me, from about three dozen different types of energy drinks to a quarter-acre of produce to patio furniture to toys to all sorts of Iowa Hawkeyes sports memorabilia. There was so much stuff available that I could hardly find the thing I actually wanted: a pre-made, pre-packaged Ploughman’s cheese sandwich that vegetarians can pick-up at practically any UK grocery store.

The Wal-Mart in Winterset had opened around 1983, staying true to its strategy of expanding primarily into rural areas to avoid large retail competitors and put those small mom-and-pop retailers, such as the Koser Brothers Dry Goods store, which sold boxes of penny candy, as well as pickles from a barrel, the Graves women’s boutique, and even the J.C. Penney — the store known by everyone’s grandmother for their cloth and curtain patterns — out of business. The “Wal-Mart Phenomenon” — including the effect of not only Wal-Mart, but the symbiotic stores clustered around it, such as Target, Lowes, Home Depot and others — resulted in a thirty-four percent decline in retail trade over ten years, according to a study by Iowa State University economist Ken Stone.

Wal-Mart opened forty-five stores in Iowa between 1983 and 1994, then took a five-year break. Five years later, another wave of store openings began bringing Wal-Mart to fifty-nine stores in fifty different communities. Stone released another study on Walmart in 2012, twenty-five years after his first, saying that sales in a control group of towns without Wal-Mart stores declined by an average of twenty-five percent. Meanwhile, by the time Wal-Mart was through with its growth, one in three independent businesses had disappeared.

Back in Winterset, the parking lot had been slowly filling up with the RAGBRAI monster buses and campers and all other manner of RAGBRAI vehicles, but the store appeared relatively empty. And when I finally found a pre-packaged cheese tray, some crackers and some hummus and carrots to eat, in addition to an extra-large package of Haribo Gummy Bears, the price exceeded the cash Dad had left me. I departed the Wal-Mart with only the tray of processed cheese at nine dollars and the crackers at two dollars. Aside from King Size bags of Doritos or Lays chips, the store had no other vegetarian option in sight — and I had already polished off a bag of those while looking for the sandwich that didn’t exist in the American Heartland. Dad turned up thirty minutes later, hot, tired and in need of a “six-pack of ice cold beer.” He handed me a twenty-dollar bill. Back into the Wal-Mart I ventured, where about twenty different King Cans of American beers — but no six-packs — boggled my mind before I grabbed a Coors Light, a Bud Light and a Miller Light, a cheaply manufactured nylon cooler and a small bag of ice. Total: fifteen dollars. It all seemed a bit pricey to me, but Dad gulped down the beer and seemed happy. I would confront the same issue three days later at a local convenience store, where two King Cans and a small bag of ice cost eight dollars. From February 2020 to July 2024, grocery prices grew a cumulative twenty-five percent and food sellers and manufacturers have passed those costs on to consumers. One Wal-Mart in Georgia, according to NPR, increased its prices by twenty-three percent. Meanwhile, wages are only up five percent, while for the lowest earners, food price hikes during the last two years have outpaced wage gains by over three-hundred forty percent. I wasn’t worried about any of that in Iowa, however. Dad was paying. We set the course for our hotel in Harlan and following showers, sought out a place to eat.

Day Three, Winterset to Knoxville: Immigration

All over Iowa — just like Germany, from which many Iowans originally hail — immigrants are moving, starting franchises of chain hotels, restaurants, and convenience stores. It’s a very American invention, the franchise, although globalized by Raymond Kroc in 1954 when he took over and expanded a local burger stand run by the McDonald brothers in San Bernardino, California. Since then, franchises have fattened up people around the world with French fries, fried chicken, greasy pizza and lots of sugary condiments. At the Comfort Inn and Suites in Des Moines, — a Choice Hotel’s Comfort brand (including Comfort Inn, Comfort Suites, and Comfort Inn & Suites) franchise owned by the daughters of Indian expats — serviced us with few questions and practically zero comments, their families putting up a million dollars in liquid capital, paying a fee up to $60,000, and giving a royalty fee of up to six percent to Choice Hotels.

As we searched for a food option, we found the only place open was called the Buck Snort American Restaurant, another chain of franchises serving mostly meat and fried food that was owned and operated by local Iowans, but serviced and cleaned by Latinos. As I picked at my Iceberg lettuce, grated cheese, and bottled Italian dressing salad, I watched a local Latino woman sweep up after Happy Hour. “If they let in some more immigrants, at least we could possibly have some better food options — they could start authentic restaurants,” I said to no one in particular, referring to the immigration crisis raging on the Southern Border. Then I turned my attention to Dad, suffering from gout and a heart condition, and watched him wolf down chicken fried steak, mashed potatoes and fried okra — his “vegetable of choice.” He seemed slightly offended, as if the kind of homestyle cooking my grandmother once proffered wasn’t good enough for me anymore.

It seemed, like most everywhere, that people from the more highly educated countries who came to America on the visa lottery — countries like India and China and even Bangladesh — somehow found their way into the business service industry, while those from war-torn countries, such as Somalia, Venezuela, Syria, and Honduras, have taken the jobs that most Americans no longer want. But I also wondered how many immigrants from Mexico, as well as South and Central America, were now calling Iowa home. As it turned out, in the last two decades, Hispanics or Latinos have become the largest immigrant group in Iowa, comprising seven percent of Iowa’s population, or 221,805 people up from less than twenty thousand in 1970. They were the ones who turned up, despite the 2006 cocktail-reception “Come back to Iowa, please” by then-governor, Tom Vilsack — directed at young Iowans who had moved away — to fill a shrinking, aging workforce. Vilsack asserted that Iowa offered more than “hogs, acres of corn, and old people,” but the campaign eventually fizzled out and Iowa’s rural industries brought in migrants to slaughter pigs, milk cows, collect eggs, and build houses and schools. I recalled in 2014 Des Moines Register headlines splashed across the front page about immigrant children landing parentless in Iowa. Those children would be high-schoolers now, and likely working in a CAFO job. Ten years later, at our nightly hotel room stops, television pundits who weren’t freaking out about the ascendancy of Kamala Harris to the presidential election were absolutely losing their minds over brown people — both legally and illegally — entering the United States. As I drove through deserted roads, up-and-down rolling hills with nothing but a few barns and miles and miles of corn stalks in sight, I wondered, didn’t this state have enough room for everyone?

Iowa certainly had plenty of room when immigrants from Germany responded to the “pull” of reports of the fertile prairies back in the mid-nineteenth century. The 1850 Iowa census reported 20,969 foreign-born Iowa residents; twenty years later, the number of foreign-born had risen to 304,692, reaching its peak in 1890 when 324,069 people landed in the port of New Orleans, Louisiana and made their way up the Mississippi River to find those who had gone before them. Tired of the Kaiser’s wars, my own great-grandparents left their homesteads in Westphalia, then Prussia, and came over in 1876 and 1890. My great-grandfather’s family left behind a seven-hundred-year-old town doing a fair trade as a Catholic pilgrimage site for Saint Ida — a cousin of Charlemagne who devoted her life to the poor after her royal husband died — where elders had built a basilica and an albergue. But his family also left a dead brother and multiple cousins who had fought in World Wars I and II. Their names are now inscribed on the St. Ida Basilica walls. My great-grandmother, the daughter of a wealthy farmer, had more to lose. Half of her immediate family left for Iowa, while the other half stayed, married off and became hoteliers, restaurateurs, bookbinders, and soldiers in the Boer War, as well as the two World Wars.

My great-grandparents didn’t have to walk hundreds of mines across deserts or pay thousands of dollars for a “mule” to package them in tractor trailers or busted boats to get by border police, but they did endure an arduous journey. Aiming to maximise their profits, ship-company owners oversold, leaving poor immigrant passengers —many of them carrying lice or other diseases — cramped in close quarters and sleeping in dank clothing and on infested hay. When they did finally reach Iowa, they found bustling train depots in Fort Madison and Burlington, rich farmland just waiting to be tilled, Catholic communities building brand-new churches and relative peace — until President Woodrow Wilson entered World War I, at least. Social support was not abundant back then, but many had family members who had gone before them — almost an essential component if one planned on staying. But if clans had enough wealth, they pooled it to start banks, equipment dealerships, and seeding and fertilizer operations. Those who didn’t, worked for someone else or joined the military — just like home in Germany — if they hadn’t already aged out before World War II. But Iowa became a central repository for German POWs, where prisoners made friends with the expats and crafted nativity scenes and other devotionals to sell at the local fairs.

The attitude is much different now. Earlier this year, the state legislature — amid a push by Trump and Republican-led states to take over enforcement of immigration from the federal government — passed a state law allowing police to charge people suspected of being in the country illegally. A federal judge temporarily blocked SF 2340, known as the “illegal re-entry” law, signed by Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds in April, which also made it an offense for people to enter Iowa after being deported from or denied entry to the U.S., or failing to depart when ordered. Storm Lake, one of the small cities in the Northwestern part of Iowa and on the 2023 RAGBRAI, has been one of the most affected by the “illegal re-entry.” From its founding, an overwhelmingly white, unionized workforce staffed the Storm Lake’s meatpacking plants, but when new owners of one particular pork plant busted the union in the early 1980s, they slashed pay and brought in immigrant laborers. Refugees from war-ravaged parts of Southeast Asia worked there first, then people from Mexico and others from Latin America. “Storm Lake is a much more interesting place today than it was in 1975 when I graduated from high school, but it’s relatively poorer than it was and that’s not the immigrants’ fault,” Art Cullen, editor of the Storm Lake Times Pilot, told The Guardian. “Everybody wants to blame the immigrant rather than blame the man.”

Before leaving Winterset, I stopped by a place not originally on my list: the John Wayne Museum. Built adjacent to the house where Marion Robert Morrison was born in 1907 — just three years before my Grandfather Brune in West Point — Morrison (who renamed himself John Wayne when he started appearing on the silver screen) was the son of a pharmacist and a homemaker who lost his American football scholarship to the University of Southern California, but found work immediately as a prop boy and then a muse to director John Ford. Wayne was Ford’s ultimate American hero — the man who oozed cowboy grit and who never left his woman, his God, or his country. And in fact, throughout most of his life, Wayne was a vocally prominent conservative Republican in Hollywood. He helped create the conservative Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals in 1944 before being elected its president in 1949. Wayne supported the Vietnam War, white supremacy (until the Blacks are “educated to a point of responsibility”), welfare-to-work, Americans’ right to take land from the Native Americans, Eisenhower, Nixon, Goldwater, J. Edgar Hoover and his good friend, Ronald Reagan for president. The gift shop, stocked with every John Wayne movie, reproduction posters, miniature John Waynes standing inside glass baubles and even some authentic props (for a small fortune), still did a bustling trade more than forty-five years after his death.

It begs the question, however: if Wayne was born anywhere else but this tiny town, would he have a museum? In fact, Wayne spent most of his childhood in Glendale, California. For someone so revered at a point in American history, few Gen-Xers, even fewer Millennials and probably zero members of Generation-Y have seen a John Wayne movie — they probably couldn’t name one, either. Still, Winterset — on the highway to Des Moines — fared better than Eldon, Iowa, another town with a famous site: the house where Grant Wood made “American Gothic” his seminal painting. While Winterset seems as if it could survive with the Wayne Museum, a couple of taverns, a few antique shops and one particular store that buys estate furniture from elderly grandmothers and restores it for someone’s “shabby chic” apartment, Eldon had lost the deurbanization battle and was well on its way to a ghost town.

I once knew Eldon well. In the 1980s and 90s, my uncle who owned the fertilizer company, lived there with his family. Just up the street from the American Gothic house, which was occupied by impoverished renters and in great disrepair until the early 1990s, stood Roseanne & Tom’s Big Food Diner, the “loose meat sandwich” restaurant started by Roseanne Barr and Tom Arnold when they decided to build a $16 million, 28,000-square-foot mansion — set to be the largest single family home in the state of Iowa. The restaurant nonetheless reignited interest in Eldon. The Gothic House was bought and restored, replete with a visitor center and another gift shop. People came and ate, maybe caught a glimpse of Tom or Roseanne, then posed in the American Gothic farm couple cutouts before picking up and traveling to their ultimate destination. But Tom and Roseanne famously broke up in 1994 and closed the diner, which had become the town’s largest employer. My uncle sold to the multinational company and Grant Wood’s moment came and went. On this last trip, nothing was open — not even the American Gothic Visitor Center. To me, all of these places seemed ripe for investment and renovation and even a bit of revolution. But the people in Iowa love Donald Trump because they don’t like or appreciate anyone telling them how to run their lives and their businesses. Tom Arnold, a loud, outspoken Democrat, moved back to Los Angeles. Probably no museum for him.

Day Four, Knoxville to Ottumwa: Cannabis Deregulation

One of the deregulations in Iowa that most people want is the access to medical cannabis and edible hemp products across the state — in fact eighty-eight percent of Americans say marijuana should be legal for medical or recreational use, according to the Pew Research Center. Ten years ago in April, Iowa policymakers made it legal to use marijuana for certain medical treatment, but since then, the same legislators who cracked the door, keep opening and shutting it, trying to regulate a drug that has been — at one point or another in its history — a key crop for the United States grown by its first president, George Washington, an 1850s pharmacy staple, classified as an illegal narcotic, and only distributed as a controlled substance. Unlike thirty-one other states, Iowa continues to arrest individuals for possessing small amounts of actual marijuana without a medical license, while neighboring Illinois, Minnesota, and Missouri has legalized all cannabis for adults. The consumable that is totally legal in Iowa? Hemp.

It makes for an incredibly confusing situation.

Hemp plants and marijuana plants look the same, smell the same, feel the same and are the same species. But hemp ( remember the rope sandals and the Grateful Dead pullovers?) is defined as a cannabis plant that contains point-three percent or less THC (Tetrahydrocannabinol — the principal psychoactive constituent of cannabis) while marijuana is a cannabis plant that contains more than point-three percent THC. Iowa legalized the sale of hemp products without necessarily specifying the amount of THC allowed, and would-be businessmen nonetheless jumped in and started producing gummies, drinks, vapes and other forms of consumables, sometimes using more than four milligrams of THC in each of their products. But in early July, the Iowa legislature passed a law that bans the sale of consumables to people under age twenty-one and requires hemp products to limit THC amounts to four milligrams per serving. Since then, hemp and head shops have proliferated across places like Knoxville, Iowa, the sprint car racing capital of the world and an overnight stop on RAGBRAI: in the strip malls next to the big box stores, in the town center next to the quilting boutiques, and adjoined to its gas stations and convenience stores.

I hadn’t heard about the cannabis phenomenon in Iowa full stop since leaving the states — only that New York and Oklahoma had legalized it — and that my father’s law firm had done most of the cannabis shop licensing in Tulsa. So as I drove from Knoxville to Fairfield to Burlington, Iowa — with my anger hitting peak over the election and Trump headlines, all the social ills I had seen, and my father’s backseat driving — I longed for a beer. Luckily, waiting for me on the last days of the ride was “Sky High,” a drink stand selling four-gram THC-infused hemp seltzer drinks for about eight dollars a can. I bought two instantly and then went back for two more. When I disclosed to Corey Coleman, the founder of Sky High, that I was so relieved to have a cannabis beverage — albeit a hemp one — to sip because of all the alcohol around, he told me that he, too, was “California sober,” meaning he was alcohol but not substance free. Corey founded Sky High in 2020 in Cedar Falls, Iowa, with his wife Taylor, and one could say they are possibly the perfect cannabis couple, devout practitioners of natural and legal alternatives for those looking for relief or “just a substitute to alcohol that’s all buzz and no hangover,” Coleman said. Coleman had been a Crohn’s patient and Taylor started her daughter, Evie, on cannabis after she was diagnosed with cancer at age two. They feel frustrated by the state’s waffling over cannabis. “(The state) had continually moved the goalposts,” Coleman said over the new limits. Governor Kim Reynolds, a Republican who aligned with Trump after her man, Ron DeSantis, withdrew from the race following the Iowa caucuses, has voiced concern over the growth of hemp products in Iowa. “I believe marijuana is a gateway drug that leads to other illegal drug use and has a negative effect on our society,” Reynolds said in 2022, while on a visit to the Alcohol & Drug Dependency Services of Southeast Iowa. She believes the burgeoning market for hemp-infused goods has taken advantage of the 2018 Farm Bill — a over-reaching law that distinguished hemp from cannabis and created a licensing and regulatory scheme for its production and sale.

But the honest-to-goodness four-plus grams of THC-laced everything is a welcome alternative to all the booze — a known carcinogen, key cause of accidental deaths, and suspected contributor to Parkinson’s and dementia — consumed everywhere in Iowa. The state department of health released a report in 2023 that found that the state is fourth-highest in the U.S. for binge drinking and sixth-highest for heavy drinking. While the pandemic resulted in record levels of statewide alcohol sales — almost $416 million in 2022 — the state report noted that as far back as 2007 that alcohol is the most frequently used mind-altering substance in Iowa. Fifty-five percent of Iowans twelve years of age or older drank regularly, and alcohol was the most cited substance of choice by people entering treatment.

RAGBRAI is almost as centered around alcohol consumption as it is around tourism. If the teams aren’t devoted to a cause, they are usually named around something beer-related: Team Daydrinkers, Team Donner Party, Team Strangebrew, or simply Team Good Beer. On paper, RAGBRAI recommends not drinking alcohol while riding, because of course, alcohol is a diuretic that also increases body temperature — and even before the climate crisis hit, overweight bodies pedalled along open roads in ninety-degree heat with little to no shade. This resulting in at least one death per year, usually from a heart attack, but also countless accidents from drunk cycling. Despite the website page devoted to healthy alcohol consumption during RAGBRAI, in 2005 a group of craft beer enthusiasts founded Team Good Beer with a mission to promote craft beer along the route. The team now has an international membership and even created a bar guide that would direct RAGBRAI riders to establishments that sold craft beer versus the watered-down lagers popular with farmers. In 2024, the event picked up a beer sponsor, Big Grove Brewery, which created Tailwind Golden Ale for its fiftieth anniversary. Lastly, however, alcohol sales are key to the towns RAGBRAI patronizes. When RAGBRAI passes through any given town, the influx of thousands of cyclists created a surge in demand for food and drinks, with eateries and alcohol vendors particularly benefiting to the tune of hundreds of thousands of dollars over their average weekly take.

Many researchers have attributed alcohol use in Iowa to the state’s German heritage, and my family certainly fits the consumption profile. In addition to the beers after the ride, my father drank sometimes up to seven scotches if not a bottle or two of wine per night, following in the tradition of my grandmother, who escaped her large family and its obligations with bottles of scotch stashed in the closet. Two of my father’s brothers had drinking problems at one point in their lives with one in-and-out of Alcoholics Anonymous at several points, opting at age seventy to start drinking again about five years after nearly dying from overturning his tractor into a pond, filling his tracheostomy with water and pond scum. He had been topping up on vodka while reaping corn for most of that day. Hayrides during family reunions were often led by uncles drinking mid-morning hairs of the dog; cousins aged fourteen or so sneaked cans of Busch Light to sip behind their parents’ backs and coerced their younger cousins — ages eight, nine, and ten into trying it. One of those cousins visited his mother, my aunt, during our stopover in Knoxville. Since my aunt’s second husband, an avid drinker, smoker, and hunter died of Covid-19 in early 2021, he has visited and cared for her regularly. During this particular visit, he brought a case of Busch Light and drank more than half of it over dinner.

Day 6, Ottumwa to Mount Pleasant: Patriotism and Healthcare

One of the qualities most associated with Americans is their patriotism, and Iowa is no doubt a patriotic and religious state, much of Christian. The Roman Catholic and the Methodist Episcopal churches both organized congregations in Iowa by 1834, and by 1836 both denominations had constructed church buildings in Dubuque or founded missions along the Mississippi River. As the 19th century passed, other religious groups had towering church steeples over the farm towns surrounding them, including the Community of True Inspiration in the Amana Colonies, the Dutch Reformed Church in Pella — a Netherlandish town in the center of the State — and the Amish. During the Civil War many churches split between northern and southern groups, even though the African Methodist Episcopal Church, founded by former slaves, was informally set up in Iowa before then. And almost all of them believed in taking up arms to defend their god and their country.

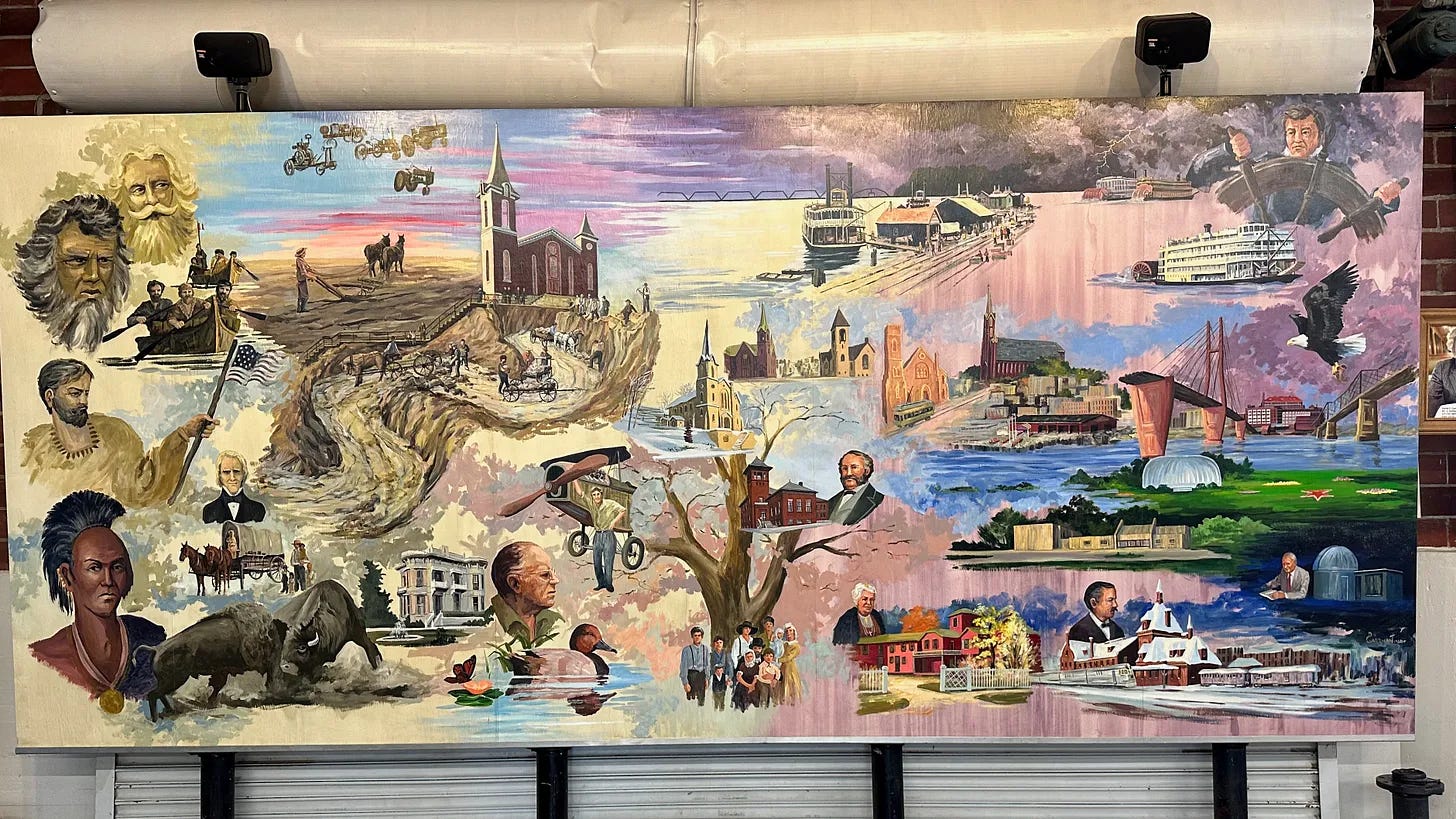

So when a man named “Bubba” began slathering paint in patriotic and military themes on massive boulders wherever he could find them — outside of towns, in town squares, on townsfolk lawns — practically everyone in the state got on board. Ray “Bubba” Sorenson got his inspiration after watching the 1999 Stephen Spielberg movie Saving Private Ryan as a 19-year-old freshman at Iowa State University. The following day, the first “Freedom Rock” made its appearance along Interstate 80. For the next 20 years, Sorenson led an ambitious quest to varnish a rock dedicated to veterans in all ninety-nine Iowa counties, calling it the ”Freedom Rock Tour.” Occasionally, there has been a race among American Legions and city councils to claim their massive ninety-ton tributes, but every now and again country supervisors find that three veterans' memorials in the shadow of the courthouses is plenty — that they don’t need a Freedom Rock — and debates occasionally erupted. Sorenson stayed out of all them, focusing instead on “the guy that worked down at the hardware store that you never knew that earned a Silver Star in Korea,” he said. Sorenson even, at one time, blended the ashes of deceased veterans into his paint — his original rock contains the ashes of nearly 100 Vietnam servicemen. But since 2018, Bubba has not had much time to focus on his rocks — or his mural painting business, Sorenson Studios — since parlaying his mission into a career as a member of the Iowa House of Representatives, serving as chair of the House Economic Growth Committee and the vice chair of the House Appropriations Committee, which oversees the funding for all of Iowa’s public programs, including money for veterans. And Iowa’s 158,976 veterans, about six percent of its population, are some of the most well supported people in the state.

In 2022, a veteran who served in the Vietnam War — the majority of the veterans in Iowa who are still alive — earned an estimated salary of forty-five thousand dollars per year and were offered such things as five-thousand-dollar grants for buying homes in Iowa, a military retirement exemption from Iowa income tax, and various other discounts, such as hunting and fishing licenses and property taxes. Iowa vets also have some of the best health care in the state. The Department of Veterans Affairs gave its two Iowa hospital systems three out of five stars overall, but the VA Central Iowa Hospital scored five stars, along with a five-star patient survey rating for veteran treatment for such conditions as cancer, diabetes, and mental health. In fact, the VA hospitals scored better than most of the other hospital systems in Iowa, including the ones operated by its universities. Moreover, while the VA receive additional funding to upgrade their medical centers, Iowa has lost more than two-hundred-fifty health care facilities in the last fifteen years, according to a report from Common Sense Institute Iowa. Iowa also has a shortage of physicians — 5,778 practicing doctors down from just 5,900 — especially in rural areas, ranking forty-fifth out of fifty states in terms of the patient to physician ratio. These include doctors for aging Baby-Boomers, as well as OBGYNs to take care of new mothers.

And while Iowa struggles to find doctors and nurses, the rates of such illnesses as invasive cancer, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s keep increasing. A 2023 report found that Iowa has the second highest rate of new cancers in the U.S., while the 2024 report found a common cancer risk factor among Iowans: alcohol. Iowa has the fourth highest incidence of alcohol-related cancers in the U.S., and the highest rate in the Midwest. Still an estimated 21,000 new, invasive cancers — cancers diagnosed as stages one to four — led by breast, prostate, and lung, will lead to the death of 6,100 Iowans in the coming year, while an estimated 168,610 people will survive. Another reason more and more Iowans are contracting cancer: twenty years of unregulated farming practices. Between pesticide use, nitrate from animal waste, obesity, and radon exposure from working in soil with uranium deposits, two in five Iowa residents, including children, will develop lung, pancreatic, and colon cancer, as well as leukemia. But a final factor contributes to all the cancer in Iowa: silence. Talking about pesticides, nitrates, radon and CAFOs are a “taboo subject” in the agricultural state. “People know what to do. We know what to do and that’s to regulate the pollution from agriculture, but it’s such a taboo subject that it’s hard to get anybody to talk, especially if they’re still working,” said Chris Jones, a retired research engineer and chemist at the University of Iowa. Another concerned Iowan, Neil Hamilton, former director of the Drake Agricultural Law Center, told England’s DailyMail that “there seems to be a surprising lack of curiosity [from] the agricultural companies and agriculturalists and farm groups … And, you know, maybe that’s predictable, because they maybe are concerned about what might be found if we started scratching a little bit deeper.” Still, with thirty million acres of land in Iowa in farming out of thirty five million, the land remains held hostage by a select few.

So does the state’s largest collective fundraiser. RAGBRAI Ride Director Matt Phippen has said he gets countless requests from cancer charities and nonprofit organizations to partner with the ride. But RAGBRAI has two beneficiaries: RAGBRAI Gives Back, which will donate about $5,000 to each of this year’s thirty-two pass-through towns, $10,000 to the seven meeting towns, and $15,000 to eight overnight towns; and the Dream Team, a program that trains underprivileged youth to ride on the cross-state trek. For the first time in 2023, however, RAGBRAI formed an entity with GoFundMe to allow riders to set up individual fundraising pages for specific causes. That policy might need to change. Like many of the counties in Iowa, the health services from Ottumwa to Mount Pleasant are run by Great River Health — a for-profit system of hospitals, clinics, pharmacies and care facilities — that, in September, started following a “provider-based” billing model for outpatient services. That means patients will receive two separate bills: one for the health care provider/professional services and a line item charge for the facility/hospital charges, including room usage, equipment, supplies, and any additional healthcare staff involved during someone’s visit or procedure. All of this, said one spokesperson “helps ensure the long-term sustainability of healthcare services in our region by meeting the financial demands of providing care.”

Day 7, Mt. Pleasant to Burlington: Religion and Racism

While my father has never supported any charity while doing RAGBRAI, he has always been a supporter of — and has likely donated a large amount of his wealth to — Catholic causes. Born in Sacred Heart Hospital in Fort Madison, Iowa, educated at St. James Catholic school, enrolled in seminary at St. Ambrose College in Davenport before serving in the Vietnam War and deciding that priest life was not for him, Dad nonetheless has attended mass every Sunday, if not every day, for nearly eighty years. Catholicism is in his blood; it runs deep within him. To see him try to prevent the decimation of all of the Catholic institutions in Iowa has, at points, been like witnessing ghost-limb syndrome.

One of the first white men to see Iowa was a priest: the French Jesuit Father Marquette, who landed near Montrose, in Lee County, where he made first contact with the Native Americans. In 1788, Julien Dubuque, a French Canadian trader, obtained from them a grant of land, which they mined for lead, while forming Iowa’s first town: Dubuque, which is also the site of the first Catholic church built by a Dominican missionary in 1836. Seven years later, the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary left Philadelphia for Iowa, as did Trappist monks from Mount Melleray, Ireland. By 1858, Iowa had forty-eight priests, sixty churches and a Catholic population of fifty-four thousand people; fifty years later, those numbers had increased five-fold with all the German immigrants. At the turn of the 20th century, the Sisters of Mercy established hospitals across Iowa, then built Mercy Medical Center in Des Moines with a nursing school adjoining. Competing orders founded more hospitals and more schools until the mid-1950s. In fact, Catholic nuns and priests educated twelve percent of all schoolchildren in the U.S. Most Catholics back then allied themselves with the Democratic party.

But since 1965, the ranks of nuns has declined by sixty-two percent, and the staff composition of Catholic schools went either lay or the schools closed their doors. “The school system had literally been built on (the nuns’) backs,” as written in the 1992 study Catholic Schools and the Common Good, “through the services they contributed in the form of the very low salaries that they accepted.” Despite a growing Catholic citizenry (from forty-five million in 1965 to almost seventy-seven million today — now the largest Christian denomination in the U.S.) Catholic school enrollment has plummeted, from five million students in nearly thirteen thousand schools in 1960 to two million in seven thousand schools by 2006. Meanwhile, Iowa has attempted to turn the tide with the Students First bill, which grants of up to $8,000 per year for parents in to use for private school tuition and fees and other educational expenses. The state, in turn, gives $1,000 per student to public schools on behalf of each student who uses the money for private school.

But is private Catholic school really better? Research suggests that Catholic schools in the U.S. have higher academic achievement than public schools, and some say they have a positive impact on the communities they serve. In the U.S., graduates of Catholic high schools are more likely to vote; achieve higher levels of earning potential; and have parents that tend to take a more active role in their student’s education. Studies also suggest that the achievement gap between students of different racial and economic backgrounds is significantly smaller within Catholic school communities — more than nineteen percent of roughly two million students enrolled in Catholic schools represent minority communities. Furthermore, the percentage of Catholic school students who will go on to attend a four-year college or university is estimated to be as high as eighty-five percent. Similarly, Catholic school students have been shown to consistently achieve improved math scores between their sophomore and senior years, as well as achieve higher academic achievement compared to their public school counterparts.

Other statistics say that private school students are more likely to experience bullying than their state-educated peers, a UK educational think tank reported. “In the wider population we often assume that a private education will have a very positive impact on a child’s development, when in reality many of its benefits result from the legacy of a privileged family background,” said Professor Sophie von Stumm, the lead author of the study, which is based on data from the Twins Early Development Study, a sample of twins born between 1994 and 1996. While private school students are less likely to have behavioural problems, a new study has found that they are fifteen per cent more likely to experience bullying during secondary school and twenty-four per cent more likely to take risks.

Anecdotally, some of the Catholic schools in Iowa already know these narratives.

Parochial education is a key staple of my family schooling. All of my aunt and uncles, many of my cousins, and many of my cousins attended Catholic institutions. When my cousin and his wife were unable to conceive, they adopted two children — one white and one biracial — and sent them to the best Catholic school in Cedar Rapids: Xavier. Xavier, a model diocesan school, receives a significant amount of money and resources, including — just last year — an architectural, construction and engineering program and building for its students. The Xavier Falcons are repeatedly at the top of the Friday Night Light football game schedule.

Both of my cousins became good athletes, the biracial one, in particular. When he had a chance to try out for school running back, his competition was a white student, a boy whose father was well-connected in the diocese. One day, my cousin opened his email to find a copy of the now infamous photo of a Minneapolis police officer killing George Floyd. Instead of George Floyd, however, my cousin’s face was photoshopped on top of George Floyd’s. The hate crime didn’t make the local newspapers or even, the local PTA meeting. My cousin’s teenager left the football team and rarely came out of his bedroom for the next year. My aunt — his grandmother — a good-hearted, generous, thoughtful Catholic woman asked us not to repeat the story. “It’s a good school with good people and I know they tried their best to make up for it.” I left out names in deference to her.

Perceived racial discrimination (PRD) is a risk factor for a wide range of undesired health outcomes across populations, particularly racial and ethnic minorities Among Black youth, PRD increases risk of mental health problems such as psychological distress, suicidal ideation, as well as psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety, and depression, according to National Institutes of Health. Moreover, males seem to be more vulnerable to the mental health effects of discrimination. In a six- and twelve-year follow up study of Black youth in Flint, MI, an increase in racial discrimination predicted worsening of anxiety and depression symptoms for male Black youth.

Day 8, Burlington to Fort Madison: Transportation and The End

One of RAGBRAI’s many main mission is to promote bicycling thruways and scenic routes throughout Iowa. So far, Iowa has twenty-five hundreds miles of trails across the state — far from the U.S.’s top cities of Minneapolis, Chicago, and Seattle, and a poor comparison to the nearly twenty-two thousand miles of trails in The Netherlands. Iowa — like most of the U.S. — is a car and pick-up state.

The Iowa Department of Transportation doesn’t keep income or racial statistic on its riders, only studies of small cities and only good ones: Iowa City's fare-free transit program saw a forty-four percent increase in ridership in the first three months. But that doesn’t solve the problems of miles between towns or people struggling to get to work and school on time, or lastly, trying to get to Iowa from another state. And lastly, it doesn’t put to rest the conclusion that Black, Latino, and other minorities are the chief users of city buses.

Iowa’s population is continuing to migrate toward the state’s nine metropolitan areas, which each have a total population of at least fifty thousand people. Within those small cities, Iowa has nineteen urban public transit systems covering about fifty-six thousand square miles. By 2050, racial and ethnic minorities in Iowa are projected to account for almost twenty-five percent of the state’s total population. Minority groups in Iowa are more likely to have a lower median household income and take a mode other than a personal automobile to work than nonminority populations. Of course, the transportation department aims to increase bus routes, provide translated transit maps, and offer more jobs to the number of people working in the transportation sector. Already, Iowa City has a shortage of bus drivers and the Des Moines Area Regional Transit Authority (DART) will cut down its buses by forty percent by next year. DART has been struggling for months to find other new funding sources to address a $2.7 million shortfall, despite being the only mode of public transportation in Iowa's capital city. That number could grow to $7.7 million, without more public funding.

Quite possibly the most relevant example of Iowa’s transportation problem became apparent on a Sunday night in Fort Madison, Iowa. I had gone for a run and decided to take a detour past the Old Santa Fe railroad. The Santa Fe's only stop in Iowa, Fort Madison was a major rail center in southeastern Iowa, which included a former passenger depot, as well as a freight station. The Santa Fe travels rolls through Fort Madison at least twenty times per day, but for one unlucky man who “thought it could be fun to travel with his daughter from New Orleans to Iowa,” nothing much else does. From the Amtrak station waiting area, I heard a “Ms., Ms.,” before I stopped to see a man smoking. “Do you have a car? Could you please help with a ride to my motel. There is not an Uber for miles and I called the police, but they are not allowed to take me.” I ran back to the hotel and found my father — who despite his RAGBRAI friendliness — was not keen on taking a unknown man six miles to a motel on the edge of town. He removed his Rolex watch and hid his wallet before the poor man climbed into our SUV and offered us twenty dollars for the trouble. My father returned to the motel the next morning and took him back to the station. The train was four hours late.

Amtrak has been working on adding new rails, and the calls for train routes to Chicago to St. Louis, Las Vegas to Los Angeles have hit fever pitch. A new rail route from St. Paul to Chicago was able to turn a profit in just eleven days, bringing in $600,000 in operating revenue during May and costing $500,000 in operating expenses. Borealis, served 6,600 passengers in the short time in which it was operational last summer. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg has called a U.S. high-speed rail network a “no-brainer” — and Amtrak is planning to introduce the new high-speed Acela in late 2024 — but the train will remain limited to Amtrak's busy Northeast Corridor between Boston and Washington D.C. via New York and Philadelphia. Another private company, Brightline, has started another high-speed rail to link Las Vegas and Los Angeles starting from 2028. Aside from that, while the total number of miles travelled by Americans has increased, miles taken on the train have remained almost stagnant in the last decades, likely because of high prices and too few as well as slow connections on the Amtrak network. Meanwhile, individual road transport is still the major way for Americans to get around. In 2022, the latest year on record, cars, trucks and motorcycles clocked in around 4.3 trillion passenger miles (miles travelled per vehicle multiplied by number of passengers).

And on August 4, my father and I — following two weeks, a dozen relative visits, some real estate business of dad’s, and as Harris and Trump on the hustings again — pulled onto Interstate-44 West back to Tulsa. It was about ninety days until the election and both candidates would circle the state many more times. But as it’s not a swing state, neither would spend much more time in the towns we had visited. Iowa’s fate is sealed: so loyal were Trump’s supporters in Iowa that 71 percent of them pollsters in January that they would consider him fit to serve as president even if he were to be convicted of a crime, which he was on May 30, becoming the first U.S. president to be convicted of a felony. They also found that loyalty to Trump in Iowa was also fuelled by a deep pessimism about the state of the country and its future prospects.

But over the course of the last eight years, Iowa has become Trump country — he is their great hope. The New York Times has credited Trump from taking Iowa from a “swing state into a GOP stronghold… No other state has shifted as hard toward Republicans in the same period.” When asked by friends how my trip to the States went, I pull out my iPhone and scroll through photos of Iowa. Three stand out: three vintage cars, adorned with life-size cut outs of Donald Trump or Donald and Melania Trump in the drivers’ seats, standing prominently in the front yard of a house just outside Knoxville, Iowa. These type of cutouts figured prominently across the state during my time there, like devotionals to the one man who they believe can save them. But if only these Iowans looked around and acknowledged how they have tarnished their communities, then maybe they actually could fix them on their own. Maybe all of America could.