The Tom Cribb Pub + a Short Story

Central London's Tom Cribb pub inspires sport stories of every variety

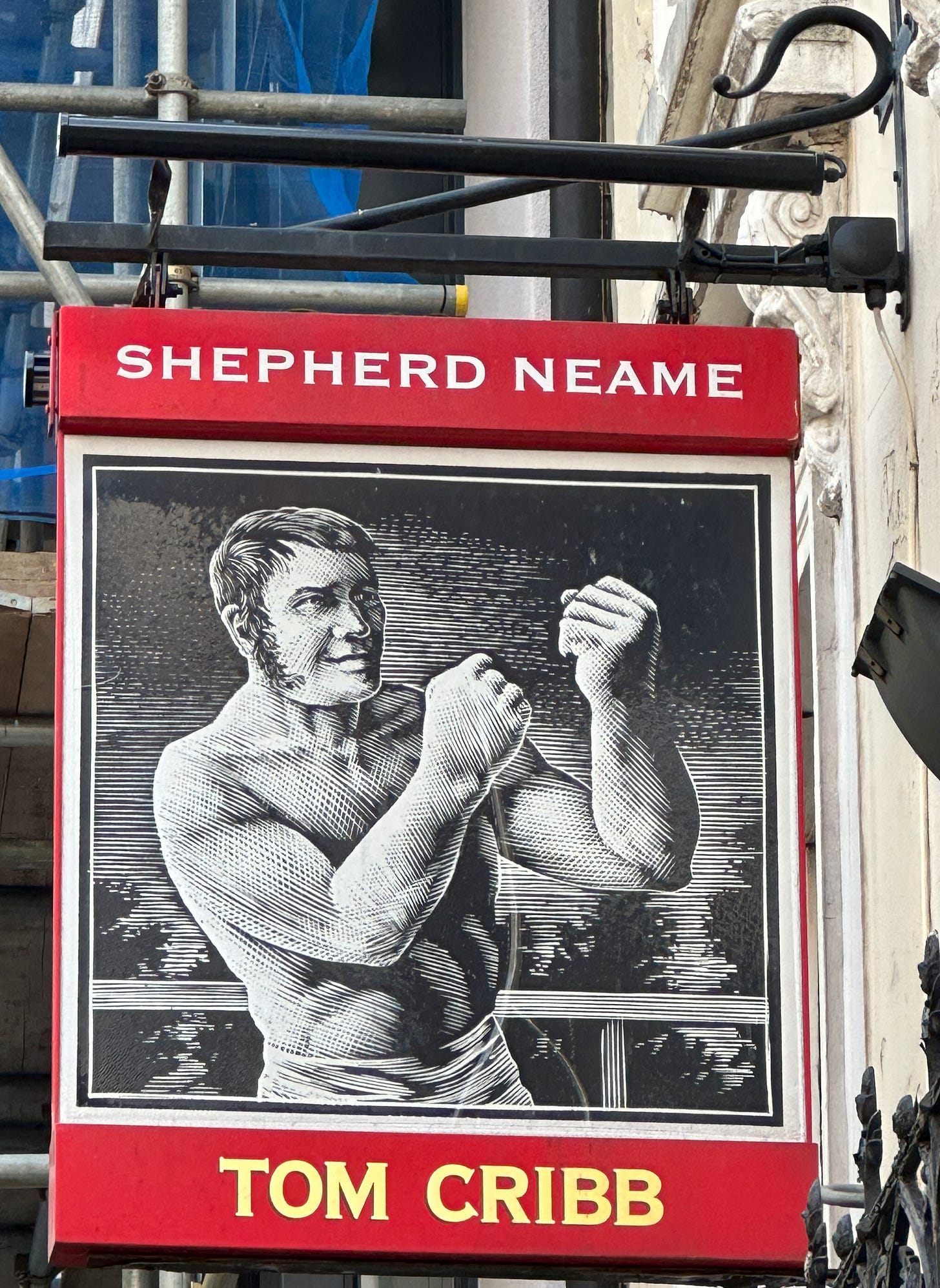

The Tom Crib pub: Central London

In the early 19th century, bare-knuckle boxing was an English obsession, and the Gloucestershire-born, Tom Cribb had only ever lost one contest and won recognition as Champion of England. He also had a pair of victories against Tom Molineaux — a former slave from America — that won Tom Crib sporting immortality. These contests, in 1810 and 1811, were arguably the first significant international contests in sporting history.

Cribb soon becamed one of the most famous men in the country. His likeness appeared in popular prints and pottery, while his name was referred to in poems, songs and works of literature — Cribb was seen as a patriotic exemplar of the virtues of strength, courage and fortitude, especially during the Napoleonic Wars. The words of the poem “A Boxing We Will Go” even imagined what would happen if Napoleon dared to take on England’s premier boxer, concluding that Cribb would “beat him like a drum / And make his carcase [sic.] sound.”

After retiring, Cribb became a coal merchant (and part-time boxing trainer), then worked as a pub landlord, running the Union Arms on Panton Street, close to Haymarket in central London. In 1839 Cribb relocated to Woolwich in southeast London where he died in 1848, aged 66. The Tom Cribb pub is located at 36 Panton Street, near St James, London — the same address as the Union Arms. In 2023, the independent family brewer and pub company Shepherd Neame unveiled an £800,000 renovation of the centuries old pub.

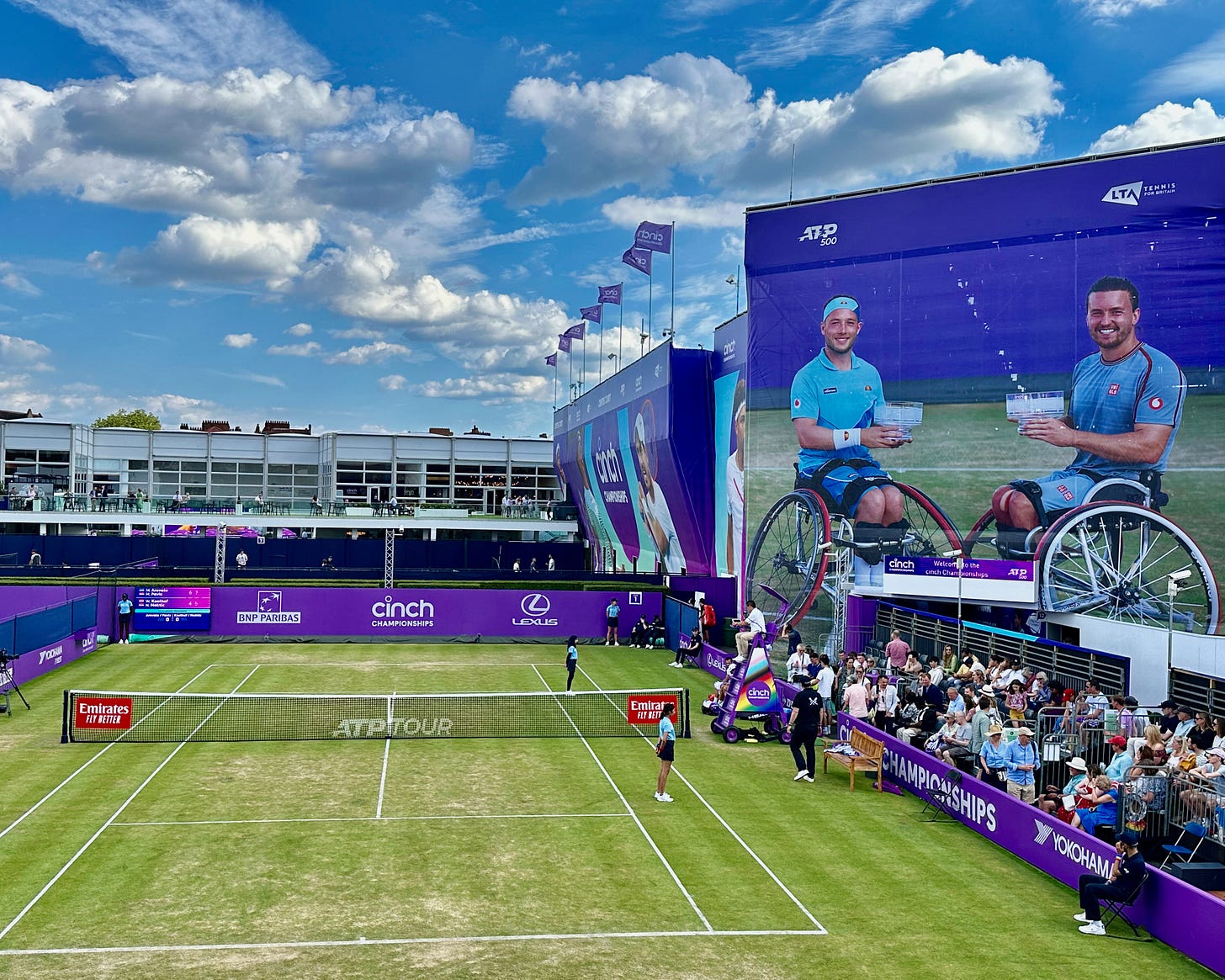

Smacked with a Racquet: My Tennis Rebirth (Working Title) Parts I + II (Part three coming this week)

About two years into my return to tennis following a twenty-year absence, I began to notice that with every match I played, I had an internal dialogue running in my head — it didn’t want to take a cue from the silent stands or the players in ready position. Topics often ranged from lustful moments with ex-girlfriends to the ugly wind-up of my opponent’s serve. On a particular Saturday in March 2019 — the early shoulder season for tennis — at a club somewhere in Long Island and while competing against a twelve-year-old during a tournament to raise my Universal Tennis Rating (UTR) (whatever that heartless data-driven, Microsoft statistic was that ignored the grace and beauty of my well-honed strokes) the two halves of my brain were having a dueling conversation that went something like “if I go for the kill, will I ruin her chances for a college spot” to “what the fuck are you doing? Close it out,” to “why are you doing this to yourself… again?”

Had my the more cut-throat and composed side of my brain sent the proper signal down my spinal cord to the leg for balance, the arm for control and the wrist for snap over the ball — as it should have — I would have jumped on her serve, hit a cross-court into corner of the baseline and boom, done and dusted, back to my Saturday afternoon. Instead, this kinder, gentler, chokier side prevailed. I started to care about her future and my tiny, diminishing role in it. And then I started to care about my own tennis prowess and the fact that I never lived up to any kind of achievement with it. I had concocted the noxious gas of tennis asphyxiation. The neural impulse stopped short somewhere between my legs and feet, which turned to cinder blocks, and my arm, which became a battering ram, determined to bang every ball with as much velocity as Serena Williams on anabolic steroids. We dragged out the match to three sets, with her finishing me off by two points in a 10-point championship tiebreak. I missed my train back to the city and had to Uber to another station, run to the train, Uber again and then home to finish out the 28 hours I had left of precious weekend “relaxation” time before the Monday commute and my editorial job at the United Nations.

What the fuck was this? I recalled thinking about my quest to rejoin the competitive classes of tennis in one of those Uber rides. My mid-life crisis? The second-chance I wanted after blowing my twenties and thirties to the New York work-hard, party harder (and drunker) life? Maybe it was some sort of extracurricular redemption, since my once promised journalism career (hello, Columbia Journalism School Class of 2002 — the one that survived to cover September 11, 2001) was going nowhere? I couldn’t quite square it. But the next weekend, during a USTA league match in the damp grit of the HardTru courts inside the West Side Tennis Club bubble, I dropped my first set 5-7 and went down in the second set 1-4, 0-30 when a primal instinct seized the hunk of meat in my cranium and said “fight.” I hit two winners, took that game and the next four and tied up the match, one set apiece. I won the tiebreak and felt something which I had become unfamiliar in recent years: exhilaration. In a year back on the circuit, I had won my first match.

I found my way back to tennis after twenty years away in a roundabout sort of fashion: I drank to the point of almost no return in my twenties, got sober in my early thirties and started running marathons as an alternative to the AA meetings I abhorred in my late thirties. Why sit in a chair and wait for a turn to gripe about your sober life when you could show up thrice weekly to the Hudson River footpath and exchange gripes while getting fit and, maybe… a runner’s high. Bonus: new running buddies and possibly weeks later another bronze finisher medal on my doorknob. After my ninth or tenth marathon, including one in Beirut and one in Lagos, Nigeria, I felt nearly invincible. My toes lost their nails and my arches ached, so possibly too invincible. But when you run and finish a long race — competing against yourself — as dozens, even hundreds of well-wishers greet you with signs, cookies, and a participatory medal at the end, it’s like hitting a ball against a wall as a kid with hundreds of cheerleaders on the sidelines. You have to be a hard-earned cynic not to feel good, and I was a converted cynic.

Still, something didn’t feel complete. I hadn’t won that medal. I hadn’t bested anyone with smooth, rhythmic strokes mano-y-mano, or in a battle of wits and muscle memory to the very bitter end. I had just shown up and run until I wanted to drop. On the day my Northwestern tennis coach cut me, the “walk on” loose, I swore off tennis for pretty much the rest of my life. Yet a hunger for the whack of the clean, crisp ball that bounced just inside the baseline remained. So did a niggly little feeling for one of those cheap gold trophies with the racquets and the servers or whatever ugly figurine the shop dreamt up. At age forty-two, I dreamt of being a middle-aged tennis champion.

From the time I turned eleven, I had wanted to be a pro tennis player. Not Venus or Serena. Not Lindsay Davenport. Not Gabriela Sabatini (although later I would have a mad crush on her and her Sergio Tacchini crinkled nylon track suits). I wanted to be Jennifer Capriati. When I was twelve and smacking forehand-and-backhand drills at Shadow Mountain Racquet Club, Jennifer, age thirteen, had worked her way into the heart of Nick Bolletieri, the grand-master of junior tennis. When I was fourteen and negotiating my way to par on a tennis court with the snobby girls of my Catholic prep school in Oklahoma, Jennifer was the talk of the United States Tennis Association. When I was fifteen and driving to lessons with my learner’s permit and my mom, Jennifer was sixteen and deciding when to go pro. When I was seventeen and competing for the number one spot on my school team, Jennifer was on the cover of every national magazine, gunning for number one in the world.

I don’t rightly know what Jennifer had to prove… self worth? But she also had an obsessed tennis dad whose own dignity was tied up in hers. I didn’t. My parents were attorneys, obsessed with their own career achieving. However, in a similar fashion, I was mirroring them. As a law school education was the great equalizer in a smallish Southwestern city still flooding with the slick, viscous profits of oil, tennis would prove my ticket to attention, respect, and maybe just a smidgeon of confidence. Although short and a bit stout, I had always been the “athletic” one in my family; if not always graceful or adroit, at least hard-working and tenacious.

But I didn’t necessarily choose tennis. Rather, I think tennis chose me. From age six, I had tried out just about every other sport: soccer, softball, basketball… coaches always pushed me to the periphery of the team. I was a mid-fielder, never a striker; outfield, never shortstop; post, never shooter. When I picked up my first tennis racquet and set foot on a court, however, I was striker, pitcher and shot-maker. I controlled my fate. It wasn’t up to the coach as to whether I played or even won. It was up to me, and me only.

I dipped my toes back into tennis competition in the summer of 2017. Before then, before the marathoning, the only bright spot during anything Alcoholics Anonymous meeting came when one of my “fellows”, a writer and high-school player from Michigan, Johanna, asked if I wanted to “have a hit” at a secret court we had found near the Atlantic Station in Ft. Greene, Brooklyn. My faded purple, torn Prince bag adorned with strips of yellow-and-red confetti still had a little plastic trowel keychain on the zipper, reminding me to “dig deep” — the words of my Northwestern coach, Lisa. Lisa liked something in me, my tenacity and my work ethic, I think, as proved by my daily bicycle rides three miles from my dorm on the South Evanston campus to a tennis bubble near the football stadium in sun, rain and snow every day to practice with never a promise to actually play. And I never played a match for Northwestern. I was the warm-up girl, the end-court solution if, one or, Allah-forbid two players got injured or sick. A season later, Northwestern gained two recruits, and I had to somehow recover from a one-point-nine GPA. I left the team. My mother wasn’t happy, but god, for sixth months of my life, I could say I was a college player. I had the keychain trowel and a thick, white sweater with an embroidered “N” to prove it. And every time I took on Johanna the writer — the two times per year I pulled out my purple bag for two decades — I could prove I had something, even though my unfit body, meant our matches were always close.

Yet, in 2008, 2009, 2011, 12, or 13, I had neither money nor energy to buy new racquets or new clothes or rejoin the USTA or find a teacher or enter any tournaments. But I had Johannah, at least, and every now and again the semi-satisfaction of balls landing with a deep thud on my long dead strings. After four years of running, however, and with a body about as close to age eighteen as I would get — thirty-plus miles per week plus cross-training — I decided I was fit enough to return to tennis. I picked my tournament: the 2017 USTA National Grass Courts at the West SideTennis Club.

I don’t remember why I decided that a nationwide, USTA sanctioned tournament on a surface on which I had never played before — grass — would make an auspicious re-entry for me. Maybe I thought, “ah, Forest Hills,” I know that place. Or I saw the words “free t-shirt.” Back in the days of old, we always got a free t-shirt for every tournament entered — I could have made a quilt out of mine. But bottom line: I was cocky. What would these club “ladies who lunch” have on me: a top-ten Missouri Valley sectional player who practiced with the Northwestern team. Plus, what I lacked in skill, I could certainly make up for in endurance. I would just grind them down in the end. Instead of two, I took ten steps forward — and then twenty steps back.

Tennis was not like riding a bicycle. Jumping back into tennis at age forty was like riding a motorbike on unpaved rural roads through jumps, ditches and knee-high grass while dodging trees and little animals. The sport seemed familiar — I had the basic mechanics — but the style of the hitting and the pace of the ball threw me off at every turn.

My first-round opponent, Christine, had come from Ithaca, New York, which she had never left after playing doubles for Cornell. Despite being married with four kids, she had also never quit playing doubles ,and doubles made her an excellent grass court player. Christine could pop off service returns and come in with the softest of touches to corner a volley or gently slice a drop shot inches from the net. I had expected the standard baseline grinder, like me. In return, I got finesse. Finesse, which in my previous life as a player I had called chip and charge ‘junk’, kept the balls sliding well below my knees and out of reach. I kept thinking I could pound cross-courts and whip down-the-lines like an 18-year-old. Except I was a 41-year-old reformed partier who had not hit a hundred cross-courts, who had not run line drills, who had not sliced a ball since 1996. And certainly not under any kind of pressure.

I learned from the first drop shot that I had woefully relied on chutzpah of the past and not my current ability. And chutzpah would not win the match. By the time she had finished, Christine had brought me to the net at least two dozen times, passed me ten, forced some 20 or so errors and left me in a sweaty, grass-stained heap on the lovely portico overseeing the Forest Hills campus.

The next hot, sunny, steamy day, with heat advisories in full effect, I played Barbara, a taller, heavier woman in her late fifties who looked a bit tamer and a bit more manageable. Based on my previous days’ battering, I didn’t expect to win, but I hoped to make the match somewhat more competitive. But Barbara had also been in regular tennis competition for about forty years. She also knew how to bait me, and I fell into every trap: over hitting, running through her drop shots, netting my own drop shots, shanking all over the place. For me, an athlete in better shape, probably twenty years younger, it was a humiliating afternoon made worse by the appearance on the sidelines of a woman whom I had been dating.

Following that tournament thrashing, I almost threw my ancient racquet bag back into the back of the closet and ended my own cliche of reigniting undiscovered talent in middle age. I still had plenty of marathons to run, I figured. Yet that drive I had long ago shoved down deep into my core had been reawakened, and I did the unthinkable for a person earning my salary: I bought new tennis racquets and booked a lesson.