The Globe Pub(s): Google vs. London A to Z

How did anyone get around in London before Google? I once knew.

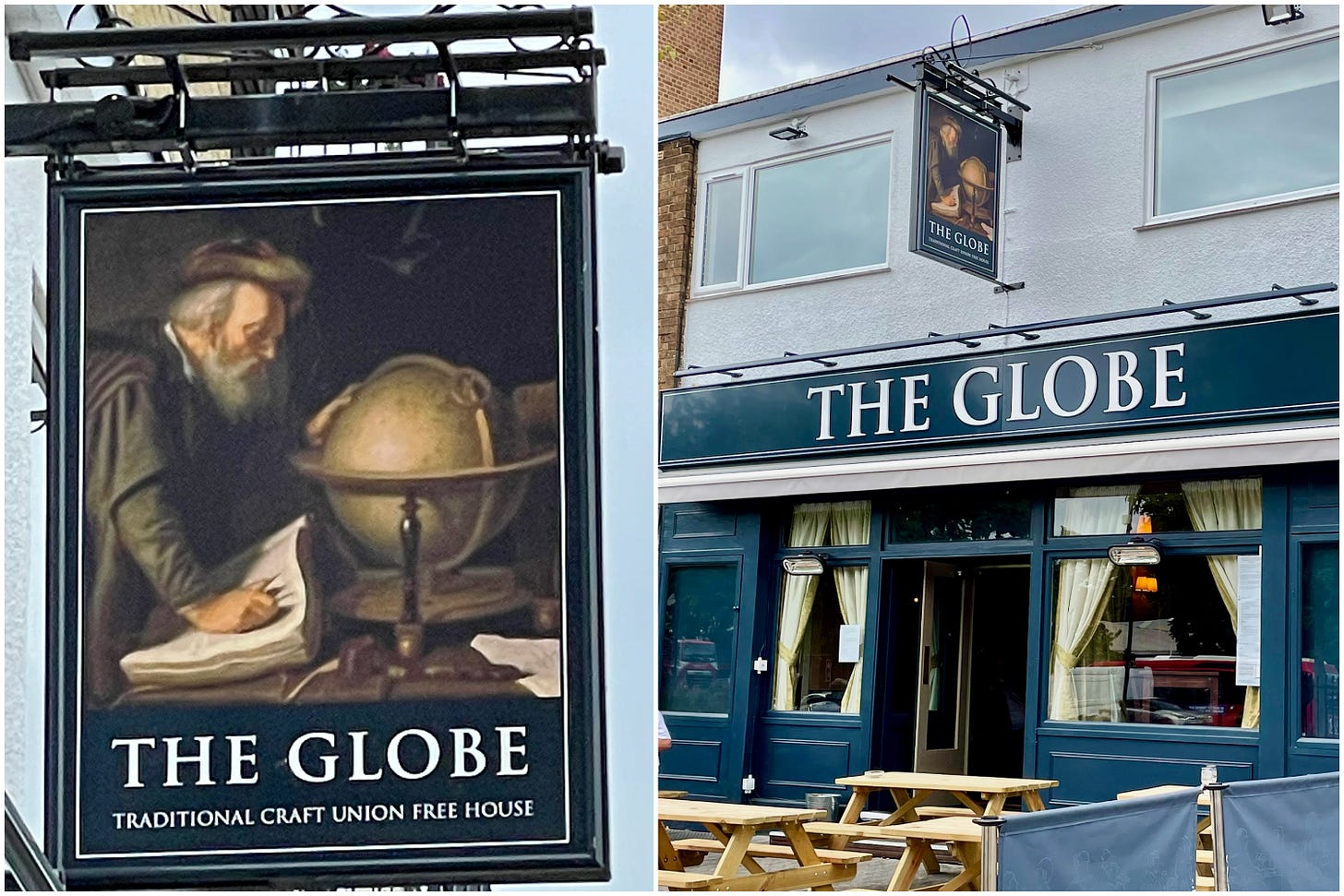

The Globe Pubs: A Common Name for a Pro-Colonisation Watering Hole

There are currently seven Globe pubs in the London metropolitan area and three within a two-mile radius of my flat in Islington. But possibly contrary to popular belief, the number of Globe pubs has not increased. There once existed more than 30 in the 19th century. And the name “Globe” comes not from the word for a 3D map — or even a pub’s central location — but from a proprietor’s desire to advertise fine Portuguese wine for drink. Yes, a globe served as Portugal’s nationwide symnol for the country’s “maritime achievements during the European Age of Discovery,” where extensive “overseas exploration took place.” In other words, the Portuguese used the globe to celebrate its feats of colonisation.

Ah, well. One can’t really live in Europe without acknowleding that colonisation may be the continent’s defining achievement.

The Green King Globe pub in Marlyebone is just opposite of Baker Street Station, and is the type of 19th century pub to which one might imagine Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson sidling up and ordering fine ale. But the location across the street from Madame Tussauds and Regents Park also makes it a prime spot for tourists, an population with which Holmes probanly would not care to hang.

The second Globe pub, located in the Hackney borough of East London and therefore, off the tourist grid, is a bit harder to locate. A Free House — meaning it serves beer from any brewery — the Globe sits just off Morning Lane and dates back to 1891. In 2021, 130 years after its founding, the Globe shut down for a few months for a £210,000 refurbishment, funded by the Stonegate Group, the largest pub company in the UK.

Lastly, The Globe pub in Moorgate dates back to the time of Charles I and the English Civil War. With its rococo exterior, The Globe — the social hub of both Moorgate and the City of London inside the former wall — sits in a prominent position on top of Roman ruins. It’s also situated close to the original site of the notorious Bedlam (Bethlem Royal) Hospital, a psychiatric institution that inspired several horror books, films, and TV series, most notably Bedlam; a 1946 film featuring Boris Karloff. The famous poet, John Keats, was also born in a stable next door.

A brief request: Journalism is still a very tough business to keep going. If you enjoy this blog, please become a paid subscriber or support me on my Go Fund Me or by buying my art on my website. Every dollar counts.

London A to Z(ed): Old Skool Google Maps

When I first came to London in the summer of 1998, Google Maps wasn’t even a cell in the minds of American computer scientists Larry Page and Sergey Brin. Mobile phones, such as the Nokia 6110, were still fairly large and solely used for calls. And London Black Taxi drivers had to somehow soak up The Knowledge, and one was advised to never get in a ride share that wasn’t a Hackney Carriage. Alas, as soon as I landed at Gatwick Airport, I picked up a paperback-sized London A to Z(ed), an Atlas of all the neighbourhoods and streets of the city first built by Rome in 43 AD.

Regarding my sense of direction, I have received mixed reviews. Some people say it’s pretty good. Give me a grid city — New York, Chicago, Tulsa — with some numbers and semi-alphabetical street names, and I can easily orient myself and occasionally, French tourists. Even Washington, D.C. and Boston, two cities designed and built by Europeans, are learnable by the likes of me within a few months. London… London was a different story. Yet, the London A to Z Atlas was supposed to solve all geographical problems. So off into the London streets — little map books in hand — went the 20 or so Northwestern summer study abroad students.

The premise of the A to Z was simple enough: 1. get the address and post code where one wanted to go; 2. use the alphabetical index in the back of the book to find said street and corresponding map page; 3. determine the street on the map page via the grid at the top and sides; 4. and lastly, situate yourself in the map and walk the streets until the destination is reached. Boom, easy. The A to Z wasn't just a map, it was “London in your pocket,” according to the Geographers’ Map Company, which published the A to Z. It even had its own version of the London Tube map

And yes, the A to Zed was, actually, a pocket-sized London — at least Central London. And getting from Holborn, where I lived, to Charing Cross or Leicester Squere, was a few turns and a stroll down Theobald’s Road. The Victoria and Albert or Buckingham Palace simply required a quick tube ride and choosing the right roundabout exit. But trouble always came when the road names changed — as they often did — but the road continued straight. Also annoying: street signs weren’t put up on nice little poles at the corner of every intersection, like they were in America. They were fastened everywhere: on the sides of buildings, on various walls and to the occasional freestanding set of short, steel posts — and never at an intersection.

I am not sure that Phyllis Pearsall, the creator of the London A to Z, ever found herself completely disoriented when emerging from a London Underground station, not even able to distinguish East or West. Or if she emphatically cursed when, say, Euston Road became Marylebone Road, or while walking down the Embankment, Grosvenor Road suddenly appeared. Or if she couldn’t understand the difference between a mews, crescent, terrace, rise or lane. But apparently, Pearsall had the same troubles. She also hated street maps that unfolded into an unmanageably large sheet of paper. Instead, she wanted a street “atlas” readable in book form.

As the story goes, Pearsall, a portrait painter and daughter of a Hungarian Jewish immigrant and cartographer (she was born Phyllis Gross — or Grosz), was en route to a party one night in 1935, when, despire using the latest map she could find, a 1919 Ordnance Survey, she got lost. Annoyed, yet inspired, the next morning she got up, hired off some draughtsmen from her dad’s cartography company and began to map the city, working 18 hour days walking 3,000 miles to check the names and house numbers of the London’s 23,000 streets that they drew up. Once finished, she was unable to find a publisher so, encouraged by her father, set up her own company, the Geographers' A-Z Map Company and self published 10,000 copies. When WH Smith ordered 1,250 copies, Pearsall delivered them herself in a wheelbarrow and only when they sold out did the other retailers catch on — the map has been in continuous production ever since.

Whether or not the wheelbarrow story is true, the A to Z is an institution. So much so, that even with Google maps, many middle-aged and older Londoners have a dog-eared London A-Z index somewhere in their shelves. Journalists, too, often find it a useful tool for quickly answering esoteric questions, such as “How many High Streets does London have” or “What are London’s most crass street names?” Although apps such as CityMapper and TfLGo (Transport for London) are the preferred choice for the majority of Millennials and Generations Y and Z, traditionalists like to point out that London A-Z books go through a carefully quality control process to: ensure more important places are drawn bigger so that they stand out (Google Maps zoom shrinks place names); standardize places like railway stations with a single symbol; and fit all road names on the page.

By 1938, Purcell had devoted most of her time keeping the London A to Z updated and in print. There were some obstacles. During World War II, when selling maps to the public was forbidden, she worked for the Ministry of Information. And In 1945, while returning from a trip to Amsterdam — where she had traveled to print a new London A to Z due to paper shortages in England — her plane crashed, leaving her with permanent scars. In 1966, Purcell turned her company, the Geographers' A–Z Map Co, into a trust to keep it from predatory buyers. The move also forever enshrined her desired standards, including the “A to Z” type-style for street names — a conspicuously hand-drawn sans-serif. Purcell kept the A to Z running until her death from cancer in 1996 at age 89.

My first London A to Z — with places hightlighted and circled, penciled notes and spine broken, disappeared somewhere among moves from Chicago to Oklahoma to Boston to New York. When I moved to my second London neighborhood, Putney, in spring 2021, I became a Google map regular, especially after I wound up in Kingston after trying to find the bicycle route in Richmond Park. This New Yorker couldn’t tap her heels three times and return to a grid. But upon relocating to Islington in early 2022 — a mile away from my old digs in Holborn — I purchased another London A to Z. I wanted to study the area, know the streets by heart and not break my phone if it fell off the thingy that held it to my bike. Most importantly, I didn’t want to have to ask the English for directions in my New York accent. The English are notoriously private, and humorists have noted that “an English town is a vast conspiracy to mislead foreigners.” Especially Americans.

That’s a fun fact, David! Thanks for sharing!

Geographers’ A-Z London edition has about 100 trap streets. Apparently they are inserted to protect copyright. If a map is plagiarised the author can identify it as a copy of his own work.

The map itself cannot have a copyright as it is a representation of fact, the trap streets and deliberate mistakes change the work from being purely factual into a creative expression and thus able to be protected by copyright.

A ‘ski slope’ once depicted in east London, although there is no evidence of there ever having been a ski slope located in Haggerston Park.

Cartographers are naturally reluctant to disclose other ’deliberate’ errors. Some are known: Gnat’s Hill for Gants Hill; Bartlett Place (incidentally the name of Kieran Bartlett, an employee at Geographers’) for Broadway Walk E14; Moat Lane off Clandon Gardens N3 which doesn’t exist; Wagon Road EN4 which changes its name to Waggon Road after crossing a railway line, but left on the map with the single g spelling.