Letter from The Virgin Queen pub

Plus Street Saviour: Ann couldn’t help herself in London. Could I? Part I

The Virgin Queen Pub in Hackney, London

This is not the first iteration of this faux-Tudor pub near Broadway Market, bridging the growing gap between the hipsterness of Hackney and Shorditch. But the Virgin Queen is possibly the most appropos name and setting for the East London local. And it attracts both highbrow and commoners, alike.

Formerly The Albion, a home away from home for West Bromwich Albion fans, the football memorabilia has been replaced by carefully sourced antique panelling and vintage furnishings (such as dark wood panelling recycled from a church), a roaring fire and hand-pumped draughts. But in 2017, Remarkable Pubs — an outfit founded in 1985 when two business men took over the run-down Prince George pub in Hackney — restored its the Albion’s architecture reset its menu and renamed it The Virgin Queen, now the 14th pub in its profile.

Originally built by West's Brewery in the 1920s, the Virgin Queen actually started life as the Duke of Sussex — good thing it’s not that any longer as the sign might feature Prince Harry and Meghan Markle and have tomatoes or other leftovers from the markets thrown at it. (See the Duke of York pub in Fitzrovia.) The open kitchen in the rear room serves delicious daily offerings and classic Sunday roasts, and Wednesday nights, The Virgin Queen hosts possibly the most difficult pub quiz in the city (won by a team pulled together by this author).

Street Saviour: Ann couldn’t help herself in London. Could I?

Ann

I was late and had a train to catch — a much-needed day excursion to the Seven Sisters National Park on the route to Eastbourne, England. But there she was in front of me, a hunched over, likely Jamaican woman on crutches, dragging three bags and kicking another though Victoria station at nine o’clock on a Sunday morning, trying to make it to the toilets. I contemplated and hoped someone would pick up the bag and help. No one did. I couldn’t let it go.

“Would you like some help?” I asked.

“Yes please,” came the reply. So I grabbed her dirty bags, walked her to the toilets and, as I had no cash, gave her my business card. “If you get in a bind, I told her, text my number. I know of a great shelter in North London that could possibly help. I used to volunteer there.” And then I found my friends, made no mention of the incident lest they think this American journalist still relatively new to the UK had “lost the plot” — in English terminology — and took off for a lovely day without a second thought. After all, I had given out my business card to sources, journalism students, other people sleeping rough and all matter of potential networking opportunities. Few had ever used it, let alone a homeless person. The day after I read all the tributes and chest-beating on social media for Pope Francis, who advocated for the poor, the criminal, those on society’s fringes, from people who never done a real day of advocacy in their lives, I had at least walked the talk. Somewhat.

Monday

After a solid walk, rested and refreshed, I awoke ready to take on the journalism industry again, pitch my articles and return to my book writing following an April of misery with the death of my favourite aunt, who succumbed to metastatic cancer, followed by a one-week trip to New York to promote a tennis start-up. I was ready to open my screen for the first time in weeks and feel the clack-clack of keys on my laptop. About three o’clock in the afternoon my phone dinged, however. It was Ann; she was in a real bind — in Bromley, of all places.

It was the last thing I ever expected. Ann would become the first actual test of my piety. Was I up for it? I had rescued a few cats off the streets of Samarkand and most recently, Baghdad — a few scratches on the hands — but all worked out. Ann would prove to be a very complex street cat.

“Is there nothing in Bromley for you, Ann?” I actually knew someone that way, a woman who ran a cat sanctuary from which I had adopted my latest eponymous moggy, Bromley, in 2022 — my personal best friend and editorial assistant. I dared not call her, however, as I was certain that she would say no and be awful — a theory proven later in the week. The woman would take in hundreds of feral animal, her home and gardens full of every type of stray imaginable, yet I somehow knew she wouldn’t provide shelter for a human being — not even in one of the kitty cottages in her backyard.

“No,” came the reply from Ann. “People are telling me that I smell and that I can’t be crawling up any stairs for health and safety reasons,” she sounded close to tears. “I’m not sure I can take much more of this; and I need to use the loi (sic).” Ann had to use the “loo” — British speak for toilet, ladies’ room, rest room. She wanted to say the highbrow thing in England’s insanely classist society. She just couldn’t spell it.

“Ok, it’s getting late. Can you make it to Islington?” I asked, figuring the answer to be “no way,” especially after I told her I had a small flat, up two flights of stairs and nothing to offer but a couch, a meal, a bath and the friendliness of Bromley and Dorothy, my recently acquired senior cat taken in out of mercy, more than anything. “Fine,” she said. Another surprise. Two hours later at Angel station, there Ann stood in her long puffer coat, pink cap, tired ballet flats with crutches and dirty bags, ready to offer the biggest embrace I had ever received from an English person I knew not at all. I took the hug and grabbed all the bags, and we set off to find her some fish and chips — the only thing she wanted to eat despite her supposed diabetes — in Chapel Market. After she literally crawled backward up my two flights of stairs and set her things on my couch, she ate and watched a few hours of Netflix — teenage dance and gymnastics dramas from Australia (not my genre). I also finally talked her into taking a bath and sorting through her dirty bags, which she eventually did. We did two loads of her laundry, and she reorganized all of her things into fresh tote bags, while I cleaned the ring of dirt Ann had left in my bathtub. She continued to watch her teen drama and play games on her phone, thinking I was having my own shower.

At some point, I fessed up to my best friend and business partner. “Okay, I would never do it, but we’re different,” said K, a pricing executive at an international agency. “Hide your jewellery.” I blanched at her remark.

“K, she had to literally crawl up my stairs, I don’t think she is going to make off with anything of mine. And if she did, I could tackle her before you could say Longines.”

“Fair point,” K acknowledged. “Just be safe, please.” I complied. Over the course of the night, information came like drips and drops from a leaky, rusty tap — water I nonetheless knew how to collect after 25 years in the media business. I gave a significantly fresher Ann my bed for the night, not knowing she actually wanted the couch. I told her we would fix her up and find her a place the next day. We said our good nights, and I texted every social worker and homeless advocate I knew, hoping — and actually praying — for a miracle.

Tuesday

I let Ann sleep until midday, until I proposed a pedicure before we hit the only social service agency anyone had sent: The Passage, a homeless charity in Westminster that supposedly dealt with the toughest cases in all of London. I wanted Ann to feel like a human being again, not like a bag of rubbish no one wanted. I knew she would get a completely unnecessary grilling from the tired case worker crunched to get meaningless data to qualify the paltry sums of earmarked money received from private donors and an austerity government. I tried mightily to give her a boost before this happened. Then I sat through the meeting with her, attempting to translate the bits and pieces of data her trauma- or illness-addled brain could manage for the social worker, who remained more stoic and graceful than I had possibly could have managed after eight hours of trying to help hopeless situations such as Ann’s.

As it turned out — and as I likely knew — this was not Ann’s first rodeo with the system of poverty in the UK. She was an excellent cattle-roper so to speak, and definitely fell into the category of “toughest cases” described by The Passage’s website. Ann was what the English call “intentionally homeless,” meaning that she had either fled from, refused to pay for or outright turned down council housing provide by the borough of Camden, one of 32 boroughs — in addition to the City of London — that make up the administrative divisions of Greater London, each with its own town council. If a London borough council finds someone intentionally homeless, it can yank its obligation to provide housing, or pass the buck to another council, or another, or another. I was beginning to understand these complications — a fairly horrific education or what Americans love to call an “ah-ha” moment.

That said, after reading articles and watching various media, including about the shoddy conditions of the Grenfell Tower council housing that caused the fire killing 70 people in 2017, I’m not sure I could blame her. She described places full of mold and infested with spiders, in addition to neighbours writing nasty, racist things on her front door. Ann knew the various patchwork of day centres and domestic violence shelters and churches with free meals that attempted to keep the “rough sleepers” existing for what seemed like posterity to me, at that point. She refused a referral to the Marylebone Project designed to keep women off the streets in the posh Westminster borough, saying that its workers provided only food and chairs and nowhere to sleep, despite its shiny, happy website, which highlighted the smattering of successes. Should they doze off, the women would be rudely awakened, she told the poker-faced, case worker at hour two of the interview. Ann wouldn’t deal with StreetLink, the homeless referral service used by every private shelter in London, either, having evidently been left by two workers in the rain after they discovered her “intentionally homeless” status. Neither I nor the case worker knew whom to trust anymore by then. I just know that I totally understood Ann’s occasional self-harming and desire to commit suicide after I heard the story. I would have.

I, personally, don’t believe in true altruism any longer. We all get something out of helping, whether it’s power, attention, a pat on the back, or a knighthood from King Charles — if anyone in the government notices. Ann gave me a feeling of usefulness or purpose, or just being liked, which I had been seeking since an extended family fight had broken out between me and the rest of my large Midwestern Catholic family over, essentially, a book of our family history started by me because I had felt unseen and unheard for decades.

My objective with Ann — as it always had been — was to find a stop gap between her cheques and her residence, help her on her feet and get her on her way. I also wanted to alleviate the grief, anxiety and an existential crisis about the point of my life following my aunt’s funeral.

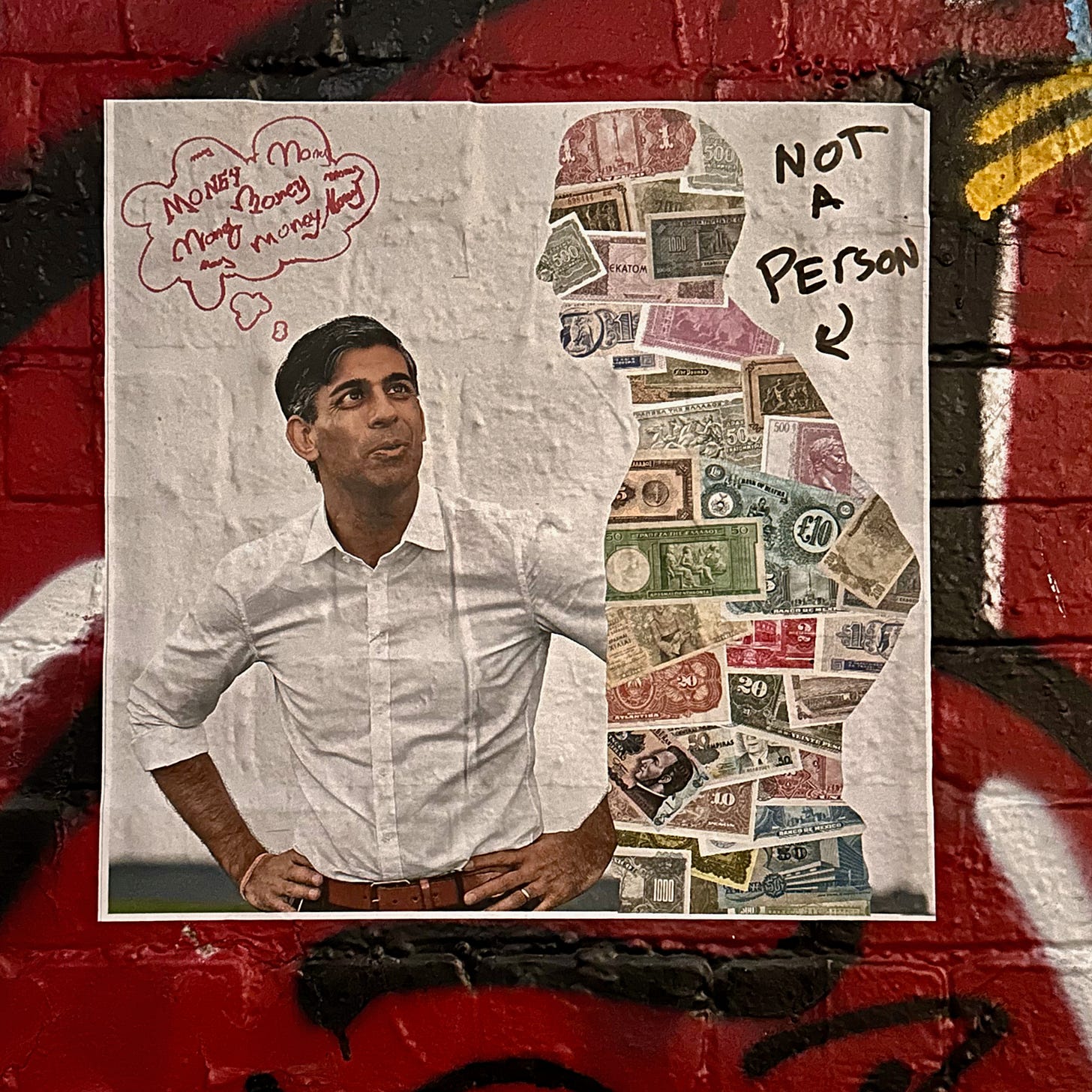

Along the way, political questions started to form in my mind, considering the situation in Great Britain and in America. Following ten years of politicians cutting the heart out of social services for all the marginalised — as church leaders, including the late pope, were trying to encourage compassion for them — are the lot of us just supposed to think that everyone on the street is just putting us all on, faking a scam to make the Roma gangs a ton of money, or that UK’s socialism lite would prevail? Should we all throw a bunch of loose change to the people on our streets and then kick them off the curb? Are the idiot, naive ones of the population supposed to take them in one-by-one and spend our own hard-earned money as the tech billionaires and politicians and lobbyists just get richer off the dysfunctional government? If we’re all supposed to be practicing radical self-responsibility as Trust Fund Baby President Donald Trump across the ocean continues to slash and burn any kind of domestic and international aide in favour of amping up for yet another war in the Middle East to create more destruction, then who the hell is supposed to look out for the people would couldn’t look after themselves? Was I supposed to invoice the government for monies spent on Ann? Which department? If someone did the same in America now, did that department still exist thanks to the absolute insanity of a certain car-and-rocket business buyer (not founder) who drove his employees like indentured servants, while he seeded the world with his offspring and encouraged more people to do so?

It also wasn’t my first tangle with homelessness, either, having been in the system for a few days myself — once a bad substance abuser in New York and Doha, Qatar, where I managed to drink myself out of a good job, been flown back and then be left to my own devices. I spent three frightening nights clutching my possessions while I slept in a shelter in East New York, one of the worst areas of Brooklyn in terms of crime, poverty and hopelessness. As a last resort, family friends from Philadelphia bought me a train ticket and put me on their couch, essentially rescuing me. But those days were hopefully long gone — or so I hoped. I had somehow curbed my love of cheap, light beer, which I could literally drink all day, allowed my family to help in the way they wanted and got sober in 2012 after four years in-and-out of Alcoholics Anonymous, which I loathed with a passion reserved only for the mean girl cliques at my hypocritical Catholic Prep School in Oklahoma — one currently connected to the current Pope Leo XIV. Until the pandemic hit in 2020, which shut down my New York City running club and other networks, I had found solace in a group of people together on a physical mission. We didn’t sit in a chair and moan about our issues; we ran and talked and worked those brain endorphins. But unlike Ann, I also had access to the means to recovery and therefore, my former life as a journalist, as the daughter of two wealthy lawyers from Tulsa, one of the richest enclaves of America thanks to the billionaires that ran the oil and gas industry for 100 years. Ann didn’t. Ann had access to well… not much.

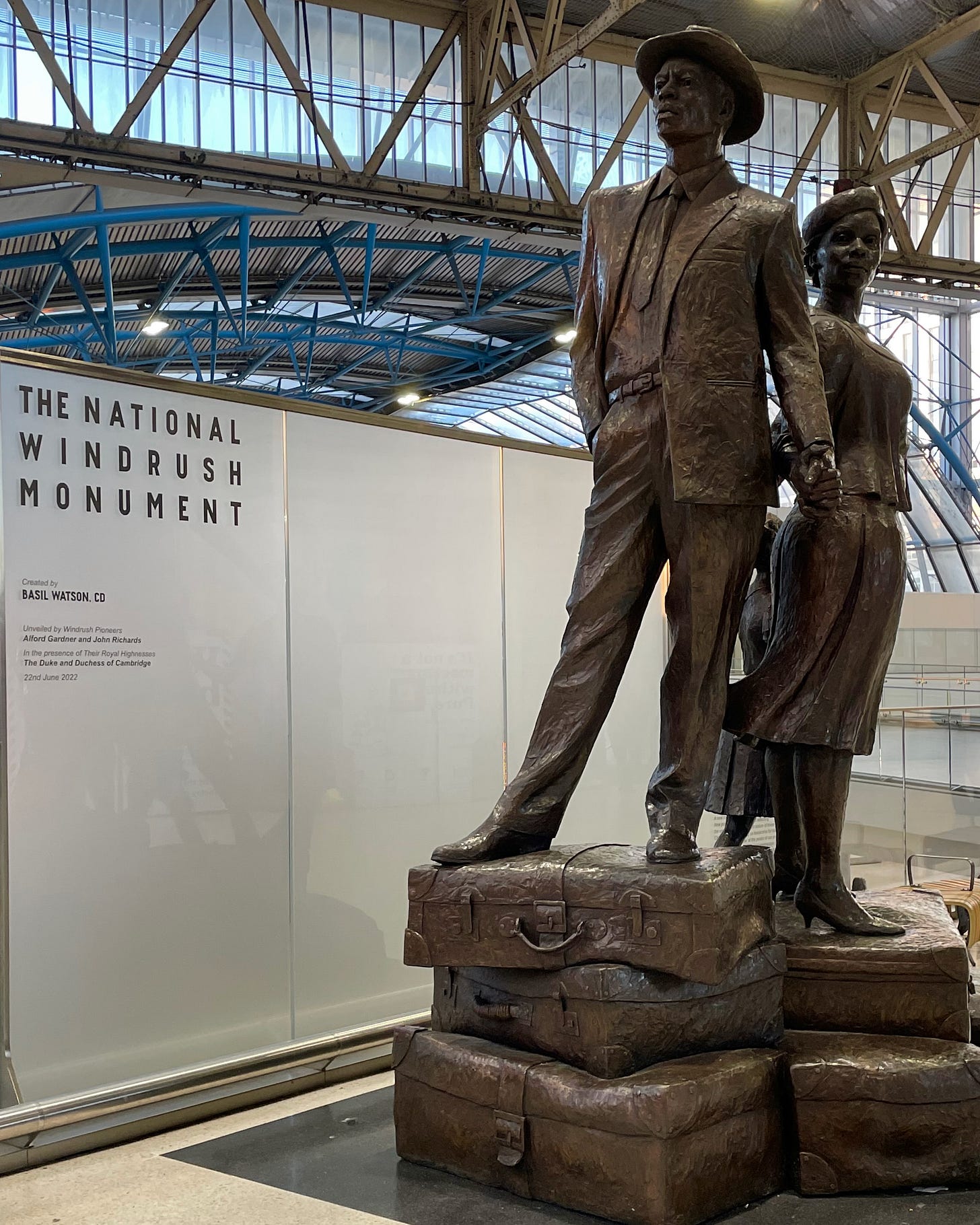

Ann had been born in London, the daughter of two Windrush workers who had taken advantage of the deal offered to Caribbean colonised nations in the 1950s: come to the home country, help our work corps, settle or eventually go back, and we’ll take care of you. While it worked out for some more than others, Ann had nonetheless been brought up well, dancing tap and ballet at one point — or so she told me — and working various jobs, including as an event planner. She even showed me the various books she had written and self-published on Amazon, an array of musings on grief, friendship and her family. Ann was neurodiverse, however, and likely didn’t care for herself well in her early years — something of which I was familiar, having drunk and partied myself into oblivion in my 20s, which was not unusual for a young journalist in New York.

Ann had two disabled brothers in Bermuda, along with aging parents who couldn’t really afford to help her. When their criticism cut, she took a verbal machete to them — an action I also knew well, having developed a knack from my own mother for sending emails that aimed for the head, and heart of a human being. Ann also suffered from chronic depression, something experienced by a significant number of journalists and creatives — and me. But again, she had nothing, whereby my family would always willingly pay for someone to help me with my anger and abandonment issues, usually with a drug and some milquetoast therapy. However, as Ann, literally 364 days my senior, was bouncing around London finding her way, with my wits and my family’s money, after grad school at Columbia University in New York, I put together a moderately successful career, in addition to acquiring a reputation as difficult and a lazy drunk. I wasn’t alone. A 2022 survey by the Canadian Journalism Forum on Violence and Trauma which interviewed almost 1,000 media workers found that 69 percent suffered from anxiety and 46 percent from depression. Since the COVID-19 pandemic and the world’s turmoil, those numbers have only risen. The best way to make it all go away: alcohol, of which I partook heartily, trying to balance a full-time magazine job with freelance writing to make all of my ends meet whilst living in Brooklyn, New York. Cracking open a beer at night was my reward for coming home from work to do more work and prove to my family that I was not the ne’er do well they thought; that I could make it on my own.

All of these thoughts crossed my mind as Ann and I sat behind the desk of Amanda, who just wanted to get through her last appointment of the day. As she tried to coax some sort of housing history out of an Ann. Ann could hardly remember one year of housing history, let alone the last five. Moreover, she outright refused to give out the phone numbers of he ex or any of the friends with whom she had falling outs over this, that or the other.

“But Ann,” I tried to cajole and coax, “this agency will just make a ten-second call to verify you exist. It’s no big deal. And those addresses, just get close to the mark and the staff will do the rest.” The social worker nodded in agreement.

“I would never want anyone giving out my number without my permission and I’m not going to do it. I still have some principles left. I am still human,” she kept reminding us, eyeing the poor girl as if she was a police interrogator and me with disdain for making her endure another round of this.

“Ann, if they’re not going to protect you, why protect them? You have to come first in this situation. These agencies just need the information to meet their own reporting requirements so they can keep receiving money from donors and the government to help people in your circumstances.” Apparently, I was hitting all the right notes as the social worker and I exchanged looks. I took pains to notice something — anything — that would win her over. I saw her white Birkenstocks and matching toenail polish, and told her how stylish it looked, that she was possibly once of the best-dressed social workers I’d seen. I felt sorry for both of them at the desk: one a once open, betrayed but still seemingly optimistic or deluded woman (or just someone that believed the website propaganda) hoping that the system would still come through for her; the other completely skeptical — possibly once idealistic — case manager knowing this appointment was already a failure.

After Amanda took as much information as she could possibly compile, we were given an email address and told to follow-up. Ann’s alternatives for the night: the Marylebone Project; a privately run shelter in North London, to which I once regularly delivered bread and vegetables, Shelter from the Storm; or my apartment again. I had heard from a friend in the social work community that Chief Executive and Co-Founder, Sheila Scott, could be surly — “difficult” in the King’s English — unbending and unwilling to help, but surely she could provide a place for Ann. I ordered an Uber, and as we drove to Shelter from the Storm, I started saying foxhole Hail Marys, hoping to find Sheila in an accepting mood.

The problem in all of this: I had come to actually like and care for Ann. She could be incredibly child-like and stubborn — a real pain in the ass and particular about her food, medicines, places and triggers. But who in this world isn’t? The night before, as I sat in my chair writing away, I would sometimes look up at this stranger on my sofa watching her badly acted, nonsensical Australian gymnastic shows marvelling at the floor routines and the balance beam acts. Or sometimes I would see her play her little phone games with glee, a grin across her face. Other times, I would notice her texting her friends and family, trying to find for herself a more suitable environment that didn’t involve too much stress. Ann was well aware that she was on the clock at my place; I had no reason to remind her. All the woman wanted was Netflix, a couch, some calm and her games, which she had told me were recommended by a therapist to counter any negative emotions. Why was this so hard to provide for her, I wondered, until I had to coax her myself to drink her laxative and take her inhalers, as if she was my child. Ann likely needed an assisted-living or nursing home.

At Shelter from the Storm, Sheila wasn’t in a magnanimous mood, as I soon discovered upon her opening of the locked door.

“Hi there, do you remember me? I used to deliver vegetables here,” I told her as an introduction.

“Yeah, and why are you here now?” she asked.

I gestured to Ann and told Sheila I had a friend who needed some help, who was slipping through the cracks, who needed a place to stay until she could receive her benefits, who was peaceful and relatively self-contained and who wouldn’t cause any trouble. Would she help?

“I have told all of you lot of volunteers that in no uncertain terms that I would not take your referrals,” she said to me before she slammed the door in my face.

“Wait, please,” I said, before I stopped her. The stress tears started the flow; Ann turned to her phone and her games. “This woman has been through hell and she has nowhere to go but my flat until her next round of benefits. She has been beaten, verbally abused, tossed around by mall security, transit workers, library staff and hospital aides.” At this point, I was down on my knees, a position to which I had not been familiar since my last Catholic mass, some eight or so years prior. “Please help her; I am begging you.”

“No, our insurance won’t allow it.”

“Please, I will be a night volunteer, as I promised before.”

“We don’t need volunteers.” An obvious lie. They needed more volunteers than they could count.

“Please, I will make a donation.”

“We don’t need donations.”

“Please, my god, have some mercy on Ann — I cannot take care of her. She is a nice lady and would be a welcome addition to your household. She is no trouble.” That’s when the dressing down really began.

“How many times do I have to tell you people that a) we are full; and b) we don’t take referrals from volunteers?” She paused and looked at Ann, then looked at me. I thought perhaps she would relent.

“Go through Streetlink or one of the other homeless teams. Then maybe I’ll consider.”

“We have. I have been everywhere. You are our last hope for today.”

“Then I suppose you have no hope.”

At that point, I had no strength left to argue or fight or even call her names — a bit unbelievable for me. I stood up, took Ann by the shoulder and walked away. “Let’s go home, Ann; how about a night of movies and phone games?” I asked, hoping she wouldn’t notice the tears. “Sounds perfect,” she replied, and we repeated the previous night’s ritual. How could someone be so cruel, I wondered? How could someone from a country that prides itself on tolerance and etiquette live with themselves after turning away a disabled, homeless woman? I would have an answer soon enough.