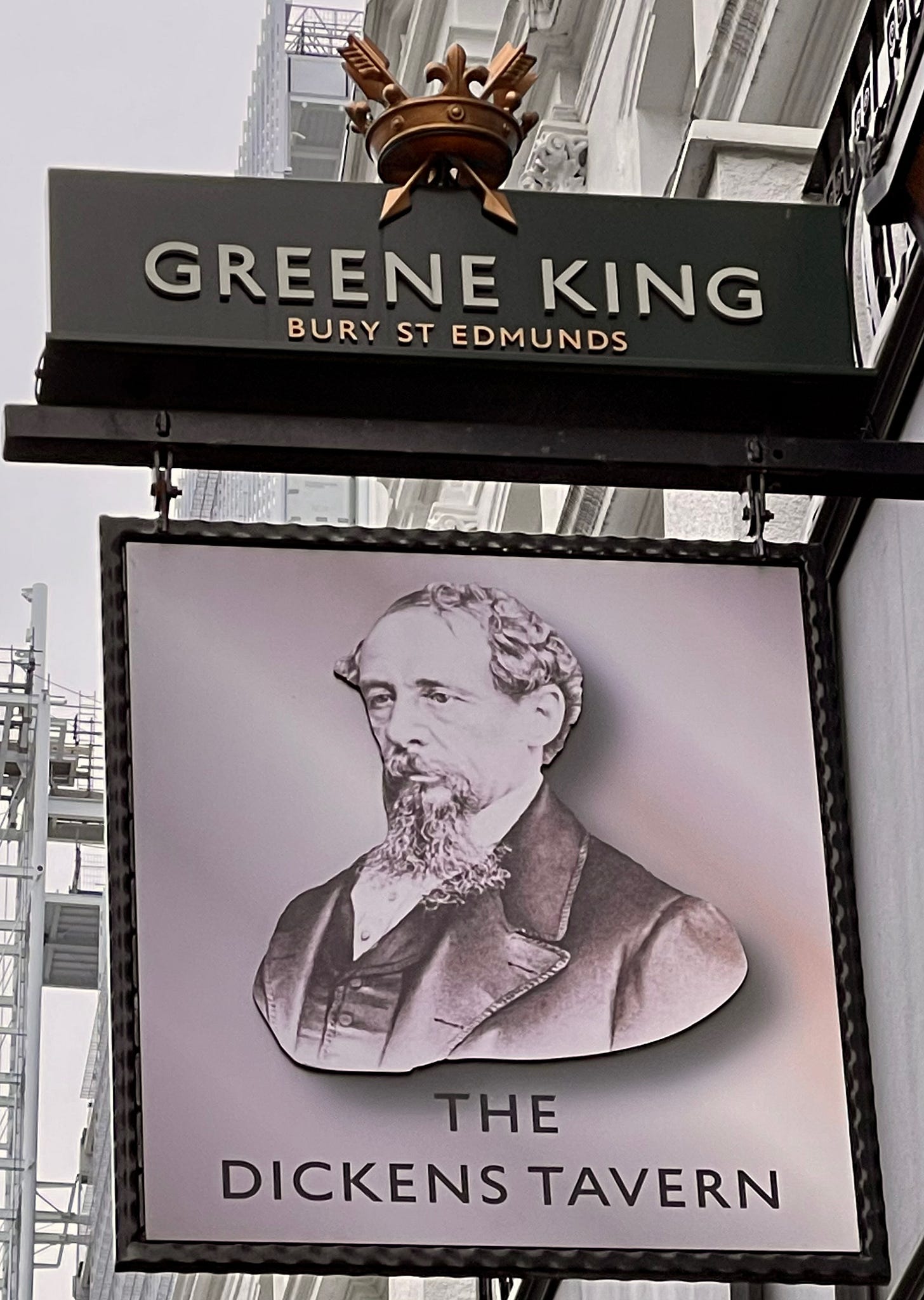

Letter from the Charles Dickens pub in Paddington

Everyone in London is under an economic squeeze, especially writers — it's downright Dickensian

All photos taken by the author.

Things are getting downright Dickensian in England. Amid a cost of living crisis, shoplifting, especially in grocery and convenience stores, has more than doubled in the past three years, reaching £8 million in 2022. Doctors, teachers, rail employees and other unions are finishing up their second year of regular strikes, keeping us all wondering if we will be able to get from A to B on time — or treated at a local surgery. The Tory government just scrapped a major rail connection from Birmingham to Manchester, proclaiming that money for this “leveling up” proposal was better spent elsewhere, perhaps on projects where the kickbacks are better for the six-figured salaried MPs.

Most places in London — or insert another major metropolitan city here — there is a new Tesla, or Bentley or chauffered Mercedes parked around the corner from someone on a corner begging for food or money for a place to stay, often with a pet in tow. The gig economy is still in full tilt, and the poor seem to get poorer, as the rich just show off more. Conspicuous consumption has everyone in its grasp. Uber drivers work longer hours to transport all the newly minted software engineers from nights at the pub, as more social influencers peddle “luxury brands” to make us average people look — and supposedly feel — better about ourselves. Meanwhile, the competition to have the latest and greatest apartment, Gagosian artowrk, pair of sneakers, or “experience” has reduced people at the top to a pack of greedy misers, cutting regular jobs from full-time to half-time, then cutting benefits, such as insurance or pension and vacation — and when that isn’t enough to satisfy the shareholders or the bottom line — just plain ol’ cutting those jobs entirely. (See Washington Post journalism layoffs today and the size of Jeff Bezo’s yacht.)

I started January 2023 knowing money matters would be tight, but nonetheless hopeful. I had good freelance prospects and a job fact-checking for Air Mail, the Graydon-Carter-founded-and-funded stepchild of Vanity Fair. Once again, I was in the throes of the gig economy, but if I could just piece together enough “gigs” — however low paying they were — I could get by. But in late March, Air Mail let me go with two week’s notice and two week’s pay: $1,200. It was harsh. However, I could rebound. I would focus on a couple of book projects, pitch some more ideas, pick up some additional tennis officiating. I would be outside more, instead of confined to a couch in my apartment all day, correcting someone else’s oversights and ensuring the media company didn’t get sued because of those mistakes. My outlook remained sunny — until mid-summer when the expenses for tennis refereeing started costing more than I earned, and I couldn’t keep up with a feed-the-beast content-creation job: four stories per week at a £1,000 per month. Burn out set in with no end in sight. Not even a two-week holiday in Germany and Italy cured the blues; worry followed me and my girlfriend and everywhere, from the cost of the budget-friendly hotels to the compact car rental.

I have been a freelance writer for more than 20 years now. I was the undervalued, pennies-on-the-dollar OG — the one whose economic framework became the model for every other job that could be qualified and/or quantified — a gig employee before the term “gig employee” become cool. While Silicon Valley helped every other company figure out how to skip out on paying salaries and social welfare for everyone else, I was living the life invented by ravenous publishers decades before them. Before Task Rabbit replaced the job of personal assistant and Angie’s List found substitutes for everyone from the local handyman to dog walker, I was compiling my income through “multiple streams.” Why pay someone a fixed salary to do a task — a person whom might occasionally sit around and breathe while waiting for the next one — when entities could just pay by the job and off-load the cost of running a home business, the expenses of travel, etc., and the time for creativity on to the actual purveyor?

The celebrated English editor, Tina Brown, actually coined the term “gig exonomy.” Tina Brown would know a gig when she saw one. Although a supposedly dedicated journalist and acclaimed writer — a woman of her people — under her watch, Tatler, Vanity Fair and the New Yorker magazines started dividing their offices into staff and contributing editorial. The latter worked from anywhere but the office, yet supplied all the material for the finished product; the former were regular employees who arrived at the office at 10 am each morning and shepherded the finished product to the newsstands. By the time Tina Brown was done at the helm of her fourth magazine, Talk, the names under the contributing masthead far outweighed the staff.

But that was ok. Contributing writers for magazines, if they worked it correctly, could still earn $2 a word; if you were Tom Wolfe, $10 a word. In addition to the money, editors at pubs like the New York Times magazine would take contributing writers, such as the disgraced journalist Michael Finkel (who fabricated an entire source in his story on diamond mining in Africa, yet still bounced back seemingly quite nicely), on shopping sprees for sat phones and safari clothing and luggage and whatever else they needed to land the story. I know, he bragged about it in a Magazine Writing class at Columbia Journalism School, which I attended before the bottom fell out.

Well, fuck the salary, I thought. This would work. But by that time, the internet had started consuming the news business. I had just finished my masters degree in journalism, a late bloomer who arrived well past the media party’s prime. Yet, I still believed I could forge a career. I even landed a coveted full-time job in Washington, D.C. in 2003, working at a LGBT newspaper at the height of the gay marriage kerfuffle. It was a salary. Whether or not I cranked out four stories or five stories per week, I still got my $500 — and I could still “gig” it for extra income — and exposure. If I came up short on either rent or food money, the payday loan company down the street was happy to give me a few hundred dollars at thirty percent interest.

When my girlfriend from DC moved back to New York, I followed, bored of the policy wonks and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington-types. The traditional news business wasn’t yet on its knees, but most people had started getting their daily news from websites and social media. Salaried jobs were getting fewer and farther-between. I took a job as a “full-time freelancer” at American Lawyer magazine — a job that didn’t offer health insurance, pension or vacation time, but paid enough to sustain a room in a house in Brooklyn and a car to drive to cover other freelance stories for the formerly great regional newspaper Hartford Courant (now laid to waste by layoffs) to once again, supplement my income. When I wasn’t in the city at the American Lawyer office — or later on, in the office of Rolling Stone working as a freelance fact-checker, or subsequently at the United Nations media office on a three-month contract — I was covering a story in Massachusetts, or Chicago, or New Haven, paying all my own expenses and trying to piece together a semblance of a life.

When a full evening of work seemed either insurmountable or unpleasurable or both, I bought six- and eventually twelve-packs of beer to keep the words flowing and my mind off the fact that I was “working.” Sure, I had to go home and write, but at least I could have a beer and chill out, I thought. I looked forward to it. Most of the bills got paid on time, and I even managed to afford a couple of luxuries: a new suit, an expensive watch, nice frames for some wall art. Soon, however, the nightly drinking became afternoon drinking and lunch drinking and morning drinking, when I couldn’t still my shaking hands to put on eyeliner for the office. I received my checks on time then, but the sheer volume of freelance work took its pound of flesh. It took me about three years — and a few brushes with deadly infections, as well as alcohol poisoning — to come out of that tailspin.

Soon enough, I fell into the largest gig economy scam there was: OZY.com. Once again between contracts at the UN, I started freelancing for a new media company that promised the “news before the news” for its customers and “fair wages for journalists.” At first, OZY.com lived up to its promise. Its founder, Carlos Watson, a Harvard-educated lawyer who became an MSNBC and CNN anchor,moved his operation to northern California, however, and before they could afford them, started putting on large all-day “big think” OZY-fests in Central Park with (paid) speakers such as Mark Cuban, Hillary Clinton and Mr. Outlier himself, Malcolm Gladwell. Soon the festivals weren’t enough and the Carlos Cult-of-Personality started to emerge, gobbling up every chance he could to appear on a stage or television, spending even more money on developing shows for PBS, the America’s national broadcaster. A year after I started contributing two articles a week for OZY.com — and waiting a month for a $2,000 paycheck — the company was going broke and doing the best it could to cover it up. OZY.com even brought in Fay Schlesinger from The Guardian to mask the problems and shore up its brand.

It didn’t work. Checks started coming six weeks to two months or more late. A freelancer from sub-Saharan Africa emailed me to ask about his payment, and when I sardonically replied that I supposed it was going to fund all of Carlos Watson’s break-out shows I got a call from Schlesinger and Samir Rao, the former Chief Operating Officer, telling me that my contract was over. When I asked for a reason, I was told that I had created too much of a problem by asking to be paid regularly and that I was not a team player, which stemmed from my comment to a fellow freelancer. In 2022, OZY.com was bankrupt and Watson and Rao indicted for fraud. Schlesinger had a soft landing back at The Guardian. Even liberals fall victim to exploitation for their own benefit.

But Schlesinger’s words stung. A freelancer who is not a team player? That was a new concept for me, since I had only ever wanted to be a team player in a newsroom full of other journalists, reporting about things that mattered, helping to inform people, and collaborating on projects trying to make change in the world. Luckily, a contract for UNICEF came through and I abandoned journalism for about two years, hardly publishing anything, aside from my Medium page. I have the curse, however, the undying hunger for journalism. Without writing, without informing, without publishing, I feel irrelevant, less than zero, a person who adds nothing to the world. It is my gift; it is my downfall. It is not sustainable in this world or this economy, not in the States, not in London, where I came to start fresh in 2021 (free healthcare) not really anywhere civilized. Michael Finkel seems to have done well enough in Montana, but… I like to be around people, and not cattle.

Now that the rest of the world has caught up and stolen the journalism playbook for employment, and we watch the Elon Musks of the world get richer than the Pulitzers or the Hearsts could’ve ever imagined, while the rest of us get squeezed harder and harder, I suppose I could take some satisfaction in saying, “see, this is what I have been living for 25 years.” But I hate watching the tech economy perfecting the gig economy to the letter, as well as the army of lawyers helping them around any legal loopholes when it comes to fair employment and fair wages. Contracts are signed, and employees are eliminated with the stroke of a pen. People who are between gigs and commit a minor crime, such as shoplifting, receive a letter weeks later from a law firm demanding $200 for stolen goods already returned. At the same time, if an individual has to ask for any kind of help, whether it’s rent, food, physical health, mental health, or just a stop-gap of some sort between gigs, he or she is deemed lazy, or weak, or effective enough to piece together their gig economy lives and keep that train wreck on the tracks.

I could write a book about the ordeals of a life in the margins, but at some point all parties will insist I stop “banging on” about it. I don’t long for the days of the robber barons or the nine-to-five grind, and to an extent, there have always been and will always be have and have-nots. But when upper-middle-class, excellently educated people like me are on their knees, begging people on Substack newsletters or GoFundMe pages to help keep their ships afloat (even with three full articles due the same week) — and the working class are getting pushed harder and faster at their low-salaried jobs — the social contract is broken. Humanity is fucked. We have become victims of our own desires, and moreover, in our own quests, victims of someone else’s even greater desires. England was supposed to be a softer, socialist landing. It really seems as if there is no turning back now.